Monat: März 2014

Wilfried Schmickler: Ich weiß es doch auch nicht – WDR Fernsehen

Wilfried Schmickler: Ich weiß es doch auch nicht – WDR Fernsehen.

Wilfried Schmickler macht seit mehr als 30 Jahren politisches Kabarett, und auch in seinem neuen Programm „Ich weiß es doch auch nicht!“ gibt es wieder unzählige Themen über die er sich leidenschaftlich aufregt. Und zwar so, wie man ihn kennt: bitterböse und kompromisslos, unbequem und hochpolitisch. Dabei ist er immer höchst unterhaltsam, gnadenlos und spricht ohne falsche Rücksichtnahme unbequeme gesellschaftliche Wahrheiten aus.

Seit über zehn Jahren gehört Wilfried Schmickler zum Stammpersonal der WDR-„Mitternachtsspitzen“. Außerdem stellt er jeden Montag um kurz vor 11.00 Uhr auf WDR 2 die Montagsfrage.

Wilfried Schmickler ist mit den vier wichtigsten Kabarett-Preisen ausgezeichnet worden: 2007 erhielt er den Prix Pantheon, den Deutschen Kabarettpreis bekam er 2008, den Deutschen Kleinkunstpreis im Jahr 2009, und 2010 wurde Wilfried Schmickler mit dem Salzburger Stier geehrt.

„Cast a cold eye on life, on death“ – An Yeats‘ Grab

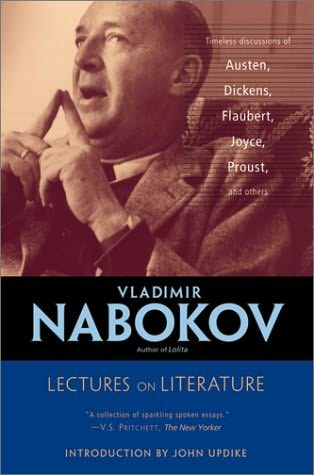

Vladimir Nabokov on Writing, Reading, and the Three Qualities a Great Storyteller Must Have | Brain Pickings

“Between the wolf in the tall grass and the wolf in the tall story there is a shimmering go-between. That go-between, that prism, is the art of literature.”

“Often the object of a desire, when desire is transformed into hope, becomes more real than reality itself,” Umberto Eco observed in his magnificent atlas of imaginary places. Indeed, our capacity for self-delusion is one of the most inescapable fundamentals of the human condition, and nowhere do we engage it more willingly and more voraciously than in the art and artifice of storytelling.

“Often the object of a desire, when desire is transformed into hope, becomes more real than reality itself,” Umberto Eco observed in his magnificent atlas of imaginary places. Indeed, our capacity for self-delusion is one of the most inescapable fundamentals of the human condition, and nowhere do we engage it more willingly and more voraciously than in the art and artifice of storytelling.

In the same 1948 lecture that gave us Vladimir Nabokov’s 10 criteria for a good reader, found in his altogether fantastic Lectures on Literature (UK; public library), the celebrated author and sage of literature examines the heart of storytelling:

Literature was born not the day when a boy crying wolf, wolf came running out of the Neanderthal valley with a big gray wolf at his heels: literature was born on the day when a boy came crying wolf, wolf and there was no wolf behind him. That the poor little fellow because he lied too often was finally eaten up by a real beast is quite incidental. But here is what is important. Between the wolf in the tall grass and the wolf in the tall story there is a shimmering go-between. That go-between, that prism, is the art of literature.

He considers this essential role of deception in storytelling, adding to famous writers’ wisdom on truth vs. fiction and observing, as young Virginia Woolf did, that all art simply imitates nature:

Literature is invention. Fiction is fiction. To call a story a true story is an insult to both art and truth. Every great writer is a great deceiver, but so is that arch-cheat Nature. Nature always deceives. From the simple deception of propagation to the prodigiously sophisticated illusion of protective colors in butterflies or birds, there is in Nature a marvelous system of spells and wiles. The writer of fiction only follows Nature’s lead.

Going back for a moment to our wolf-crying woodland little woolly fellow, we may put it this way: the magic of art was in the shadow of the wolf that he deliberately invented, his dream of the wolf; then the story of his tricks made a good story. When he perished at last, the story told about him acquired a good lesson in the dark around the camp fire. But he was the little magician. He was the inventor.

What’s especially interesting is that Nabokov likens the writer to an inventor, since the trifecta of qualities he goes on to outline as necessary for the great writer — not that different from young Susan Sontag’s list of the four people a great writer must be — are just as necessary for any great entrepreneur:

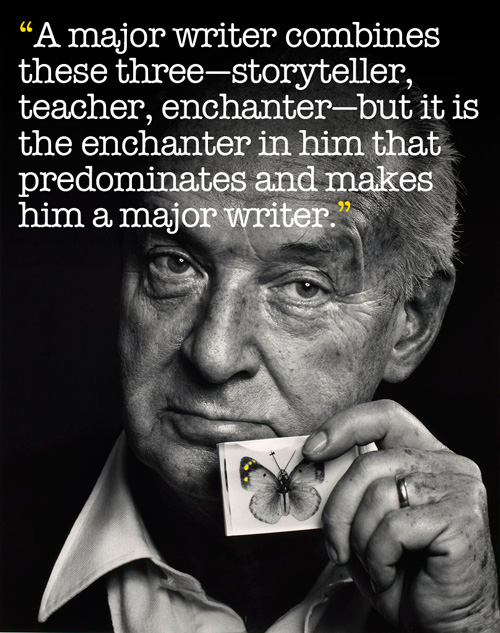

There are three points of view from which a writer can be considered: he may be considered as a storyteller, as a teacher, and as an enchanter. A major writer combines these three — storyteller, teacher, enchanter — but it is the enchanter in him that predominates and makes him a major writer.

To the storyteller we turn for entertainment, for mental excitement of the simplest kind, for emotional participation, for the pleasure of traveling in some remote region in space or time. A slightly different though not necessarily higher mind looks for the teacher in the writer. Propagandist, moralist, prophet — this is the rising sequence. We may go to the teacher not only for moral education but also for direct knowledge, for simple facts… Finally, and above all, a great writer is always a great enchanter, and it is here that we come to the really exciting part when we try to grasp the individual magic of his genius and to study the style, the imagery, the pattern of his novels or poems.

The three facets of the great writer — magic, story, lesson — are prone to blend in one impression of unified and unique radiance, since the magic of art may be present in the very bones of the story, in the very marrow of thought. There are masterpieces of dry, limpid, organized thought which provoke in us an artistic quiver quite as strongly as a novel like Mansfield Park does or as any rich flow of Dickensian sensual imagery. It seems to me that a good formula to test the quality of a novel is, in the long run, a merging of the precision of poetry and the intuition of science. In order to bask in that magic a wise reader reads the book of genius not with his heart, not so much with his brain, but with his spine. It is there that occurs the telltale tingle even though we must keep a little aloof, a little detached when reading. Then with a pleasure which is both sensual and intellectual we shall watch the artist build his castle of cards and watch the castle of cards become a castle of beautiful steel and glass.

Indeed, as important to the success of literature as the great writer is the wise reader, whom Nabokov characterizes by a mindset that blends the receptivity of art with the critical thinking of science:

The best temperament for a reader to have, or to develop, is a combination of the artistic and the scientific one. The enthusiastic artist alone is apt to be too subjective in his attitude towards a book, and so a scientific coolness of judgment will temper the intuitive heat. If, however, a would-be reader is utterly devoid of passion and patience — of an artist’s passion and a scientist’s patience — he will hardly enjoy great literature.

Agio Pavlo

Sehnsucht nach Wirklichkeit

Das Cover seines Buches „Der Schatten des Fotografen“ zeigt eine scheinbar idyllische Situation. Eine Frau watet durch flaches Wasser. Die Sonne scheint. Dass es aber ein Foto mit einer ganz anderen Geschichte ist, erzählt Lethen. „Dieses Bild wurde von einer Hamburger Kunsthistorikerin gefunden, die nach Landserfotos fahndete, die an der Ostfront gemacht worden waren. Merkwürdigerweise fand sie dieses Bild in drei verschiedenen Alben und Schuhkartons. Immer dieses Bild. Sie konnte sich einen Zusammenhang gar nicht vorstellen. Das wurde ihr unheimlich.

- „Die Wissenschaft, in der ich arbeite, ist natürlich eine Sphäre des Verdachts, wo von Wirklichkeit zu sprechen eigentlich schon eine Sünde ist, ein wissenschaftliches Versagen“, sagt Helmut Lethen. „Das Buch ist eine Polemik gegen die Sphäre des Verdachts, quasi ein Plädoyer für ‚common sense‘, dass die Medien in unseren Austauschsystemen eine außerordentlich große Rolle spielen.“

(Helmut Lethen)

Helmut Lethens Buch ist eine Einladung zum Nachdenken über Bilder. Und auch darüber, wie wenig ein Bild alleine sagt. Ein berühmtes Foto von Robert Capa, „Landung am Omaha Beach“, wurde erst durch einen Belichtungsfehler im Labor zur Ikone. Überhitzung gab dem Foto die scheinbare Authentizität. Unscharf, verschwommen, genau so war es am D-day. War es so? Die großen Kriegsfotos von heute würden mit dem Handy gemacht und je schlechter die Qualität, umso authentischer wirkten sie, sagt Lethen. „Das ist produktionell ein Überschuss an Gegenwart. Und in diesem Überschuss an Gegenwart müssen wir skeptische Schneisen schlagen, um uns überhaupt orientieren zu können. Und so pendeln wir immer zwischen der Sehnsucht nach der Wirklichkeit auf der einen und der Skepsis, dass alles nur artifiziell ist, auf der anderen Seite.“ Die Sehnsucht nach dem Echten – der Skepsis können wir nicht entrinnen. Doch manchmal hilft uns ein Bild, einen Bruchteil der Wirklichkeit zu erfassen.

„Das Menschenmögliche zur Sprache bringen“

Im Folgenden ein paar Zitate aus dem Gespräch von Insa Wilke mit Christoph Ransmayr in dem Buch ‚Bericht am Feuer‘ (2014):

‚Ich fühle mich dann vollständig und mit alles Fasern am Leben, weil das Schreiben dann ohne jeden Zweifel ganz und gar meine Sache ist.‘

‚Nur wenn ich eine Ahnung davon habe, wie ungeheuerlich der Raum des Verschwindens ist, kann ich die Umrisse der Sehnsucht nach Unvergänglichkeit und Bleiben skizzieren.‘

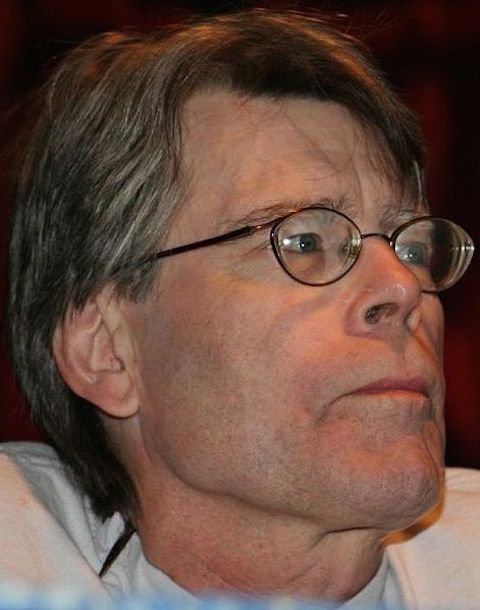

Stephen King Creates a List of 96 Books for Aspiring Writers to Read – Open Culture

Stephen King Creates a List of 96 Books for Aspiring Writers to Read – Open Culture

I first discovered Stephen King at age 11, indirectly through a babysitter who would plop me down in front of daytime soaps and disappear. Bored with One Life to Live, I read the stacks of mass-market paperbacks my absentee guardian left around—romances, mysteries, thrillers, and yes, horror. It all seemed of a piece. King’s novels sure looked like those other lurid, pulpy books, and at least his early works mostly fit a certain formula, making them perfectly adaptable to Hollywood films. Yet for many years now, as he’s ranged from horror to broader subjects, King’s cultural stock has risen far above his genre peers. He’s become a “serious” writer and even, with his 2000 book On Writing—part memoir, part “textbook”—something of a writer’s writer, moving from the supermarket rack to the pages of The Paris Review.

Few contemporary writers have challenged the somewhat arbitrary division between literary and so-called genre fiction so much as Stephen King, whose status provokes word wars like this recent debate at the Los Angeles Review of Books. Whatever adjectives critics throw at him, King plows ahead, turning out book after book, refining his craft, happily sharing his insights, and reading whatever he likes. As evidence of his disregard for academic canons, we have his reading list for writers, which he attached as an appendix to On Writing. Best-selling genre writers like Nelson DeMille, Thomas Harris, and needs-no-introduction J.K. Rowling sit comfortably next to lit-class staples like Dickens, Faulkner, and Conrad. King recommends contemporary realist writers like Richard Bausch, John Irving, and Annie Proulx alongside the occasional postmodernist or “difficult” writer like Don DeLillo or Cormac McCarthy. He includes several non-fiction books as well.

King prefaces the list with a disclaimer: “I’m not Oprah and this isn’t my book club. These are the ones that worked for me, that’s all.” Below, we’ve excerpted twenty good reads he recommends for budding writers. These are books, King writes, that directly inspired him: “In some way or other, I suspect each book in the list had an influence on the books I wrote.” To the writer, he says, “a good many of these might show you some new ways of doing your work.” And for the reader? “They’re apt to entertain you. They certainly entertained me.”

10. Richard Bausch, In the Night Season

12. Paul Bowles, The Sheltering Sky

13. T. Coraghessan Boyle, The Tortilla Curtain

17. Michael Chabon, Werewolves in Their Youth

28. Roddy Doyle, The Woman Who Walked into Doors

31. Alex Garland, The Beach

42. Peter Hoeg, Smilla’s Sense of Snow

49. Mary Karr, The Liar’s Club

53. Barbara Kingsolver, The Poisonwood Bible

54. Jon Krakauer, Into Thin Air

58. Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It and Other Stories

62. Frank McCourt, Angela’s Ashes

66. Ian McEwan, The Cement Garden

67. Larry McMurtry, Dead Man’s Walk

70. Joyce Carol Oates, Zombie

71. Tim O’Brien, In the Lake of the Woods

73. Michael Ondaatje, The English Patient

84. Richard Russo, Mohawk

86. Vikram Seth, A Suitable Boy

93. Anne Tyler, A Patchwork Planet

Like much of King’s own work, many of these books suggest a spectrum, not a chasm, between the literary and the commercial, and many of their writers have found success with screen adaptations and Barnes & Noble displays as well as widespread critical acclaim. For the full range of King’s selections, see the entire list of 96 books at Aerogramme Writers’ Studio.

via Galleycat

Interview with John Banville, a portrait in ‚The Guardian‘ and more…

Extraordinary interview with the Irish writer John Banville for the German literature TV show ‚Das blaue Sofa‘ from 7th Mar 2014 about his latest novel ‚Ancient Light‘ from 2012 that is published now in Germany.

“All art is an attempt to capture the moment,” he tells me “to stall time in its terrifyingly unstoppable flow. Memory is a kind of back-door way of doing that. But I no longer believe that we remember – I think we invent, and take our inventions for ‘what really happened’. It’s a harmless and consoling bit of self-deception.”

“Oh, of course, one never gets anywhere near what one set out to do. A novel is a wilful beast, and keeps insisting on its own agenda. And language is a terribly slippery, treacherous medium. As I always say: we think we speak, whereas really we are spoken.”

„It all starts with rhythm for me. I love Nabokov’s work, and I love his style. But I always thought there was something odd about it that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Then I read an interview in which he admitted he was tone deaf. And I thought, that’s it—there’s no music in Nabokov, it’s all pictorial, it’s all image-based. It’s not any worse for that, but the prose doesn’t sing. For me, a line has to sing before it does anything else. The great thrill is when a sentence that starts out being completely plain suddenly begins to sing, rising far above itself and above any expectation I might have had for it. That’s what keeps me going on those dark December days when I think about how I could be living instead of writing.“

I love the first sentences of Banville’s ‚The Sea‘: „They departed, the gods, on the day of the strange tide. All morning under a milky sky the waters in the bay had swelled and swelled, rising to unheard-of heights, the small waves creeping over parched sand that for years had known no wetting save for rain and lapping the very bases of the dunes. The rusted hulk of the freighter that had run aground at the far end of the bay longer ago than any of us could remember must have thought it was being granted a relaunch. I would not swim again, after that day. The seabirds mewled and swooped, unnerved, it seemed, by the spectacle of that vast bowl of water bulging like a blister, lead-blue and malignantly agleam. They looked unnaturally white, that day, those birds. The waves were depositing a fringe of soiled yellow foam along the waterline. No sail marred the high horizon. I would not swim, no,not ever again. Someone has just walked over my grave. Someone.“

John Banville: a life in writing

- The Guardian, Friday 29 June 2012 22.55 BST

Just before Christmas last year Caroline Walsh, John Banville’s successor as literary editor of the Irish Times, died unexpectedly. „It was a great shock to all of us,“ he says. „It’s a cliché but she was full of life. It’s hard to believe that she’s gone. I thought I saw her the other day when I was walking around Dublin. I had to remind myself she’s dead. Death is such a strange thing. One minute you’re here and then just gone. You’d think there would be an anteroom, a place where you could be visited before you go.“

Banville dedicated his new novel Ancient Light to Walsh. Although the book was completed before her death, the dedication is fitting. The novel aches with the narrator’s sense of loss for two women: one his dead daughter, the other a lover about whom he reminisces 50 years after their affair in an Irish coastal town. Sixtysomething actor Alex Cleave and his wife still mourn their daughter Catherine, „our Cass“, who apparently killed herself 10 years earlier in Italy.

Cleave recalls that when Cass was little she said she would marry her father and they would have a daughter just like her, so that if she died he would not miss her and be lonely. He resorts to other tricks to mitigate his grief, imagining a multiplicity of universes in one of which Cass did not die, or writing her back to life: „All my dead are alive to me, for whom the past is a luminous and everlasting present; alive to me yet lost, except in the frail afterworld of these words.“

Cleave also recollects his summer-long affair when he was 15 and his lover 35. The book begins: „Billy Gray was my best friend and I fell in love with his mother.“ But is Cleave remembering the affair or making it up as he goes along, victim of what he calls Madam Memory, that „great and subtle dissembler“? In a sense, it doesn’t matter. The important thing is his probably unfulfillable yearning: „I should like to be in love again, I should like to fall in love again, just once more.“

Where did that story come from, I ask the author, hoping for a real-life story of a teenage Banville’s sexual initiation by an Irish version of Anne Bancroft’s Mrs Robinson. After all, Banville, 66, is roughly as old as his narrator. „Oh, I’ve no idea. The problem with doing an interview is that the person who wrote the story ceased to exist every day I got up from the desk. When you’re writing there’s a deep deep level of concentration way below your normal self. This strange voice, these strange sentences come out of you. When I was young I thought I was in control of everything. Now I realise it’s much more a process of dreaming.“

Banville is fond of the characters he’s dreamed up, especially the remembered lover, Mrs Gray. „I like her. She constantly laughs at him. That, not the sex, would have helped him grow up. To be laughed at by a grown-up woman is one of the great experiences of life – I mean laughed at fondly.“ Howard Jacobson once wrote that his ambition was to see women’s throats – to make them laugh so much they hurled back their heads in pleasure. „That’s a lovely notion,“ Banville says. And then, typically, he has a story to trump it. „Once I was having lunch with a woman friend of mine, and there had been some things in the paper about my marriage breaking up – I had a bad reputation.“ (Banville is married to the American weaver Janet Dunham, whom he met while travelling in the US in 1968 and with whom he has two sons; he also has two daughters from his relationship with Patricia Quinn, former director of the Arts Council of Ireland.) „There were two women at the next table, and my friend was laughing so much that from where they were sitting it looked as if she was weeping. When they left they looked at me as if to say: ‚There you go he’s doing it again.‘ What a monster I must be.“

Could the affair in the new novel have been narrated from Mrs Gray’s point of view? „I don’t think so because I’ve never understood women. Never will, don’t want to. I’m in love with all of them, always have been fascinated by them. Not just for sex but because they always do the unexpected – at least I don’t expect what they do. They say: ‚We’re ordinary, we’re just like you.‘ I say: ‚You’re not. You’re magical creatures.‘ I’m a hopeless 19th-century romantic.“

We’re lunching at a Dublin restaurant the day after Ireland’s footballing humiliation by Spain. A nation, Banville excepted, mourns. „I was at a party once and everybody was talking about some soccer game. Apart from Harry Crosbie, an entrepreneur. He leaned across to me and said: ‚Imagine caring who won.‘ I said to him: ‚Friends for life, Harry. Friends for life.'“

So forget football and tell me about the psychic wound that made you a writer. „Seamus Heaney tells this wonderful story,“ Banville replies. „He was talking to a Finnish poet, who was rather dour as Finnish poets tend to be and said he was having terrible troubles with his parents. The poet said: ‚What about you?‘ Seamus said: ‚I rather liked my parents.‘ The poet said: ‚You really have a problem!‘

„Like Seamus, I rather liked my parents. Lower middle class, small town.“ Banville was born in Wexford in 1945. He once said he didn’t bother memorising Wexford’s street names, so sure was he that he’d leave fast and never return. Ironically, he’s returned to plunder that childhood frequently. „Sat in the fields reciting Keats to the skylarks. My brother was eight years older than I was. He was in Africa when I was a teenager. My sister was working in Dublin. So I was an only child most of my teenage years. Adored by my mother, tolerated by my father. If there is a psychic wound there, I’m their psychic wound. I must have been the most hideously irritating teenager. I thought I was smarter than them. I wouldn’t have tolerated me if I’d been them.“

Banville started writing aged 12, after being bowled over by Joyce’s Dubliners. He tapped out Joycean pastiches on Aunt Sadie’s Remington typewriter. One began: „The white May blossom swooned slowly into the open mouth of the grave.“ „The arrogance! I knew nothing of death.“ He also painted. „Couldn’t draw, no sense of draughtsmanship or colour.“ But painting at least made him look intensely. He avoided university. „I thought I knew it all.“ Instead he got a job as a clerk at Aer Lingus. The job gave him freedom to write and opportunity to travel. „I would write at night after a day’s work. I was very disciplined. I’d given up Catholicism in my teens but something of it stays with me. I try to create the perfect sentence – that’s as close to godliness as I can get.“

Later, he worked as copy editor first for the Irish Press and then the Irish Times, writing by day, subbing at night. „Graham Greene was right. He said that if you’re going to be a novelist, working as a subeditor is the perfect job. You write during the day, go to work at night, the best of your energy is during the day. An old editor of mine said subeditors were people who change other people’s words and go home in the dark.“

His first book, Long Lankin (1970), was a collection of short stories and a novella. Within three years he had published two novels as well, and reckons that the second, Birchwood, led him up a literary dead end. „It was my Irish novel and I didn’t know what to do next. I thought of giving up. I hated my Irish charm. Irish charm, as we all know, is entirely fake.“ Instead, he reinvented himself as a European novelist of ideas, writing novels involving Renaissance scientists. Doctor Copernicus, Kepler and The Newton Letter were, he argues, books written by a self-confident man from whom he sounds estranged. „Had he been to university, some professor would have warned him off those subjects. But I was free because arrogant, arrogant because free. Some say those are my best books. I think I took a wrong turning with them. Today if I can write a sentence that captures the play of light on a wall, I’m happy.“

He reckons to have had a nervous breakdown while writing Mefisto (1986), the planned fourth part of that scientific tetralogy. „It was then that I stopped trying to be in control and trusted myself to dream in my writing.“ When the book was critically ignored, he retreated wounded to his garden and grew lettuces for a summer.

Banville once said of his books that „I hate them all“. Is that affectation? „They embarrass me because they’re all failures. We’re aiming for perfection and never attain it. It’s become a cliché but, as Beckett wrote, ‚Fail again. Fail better.‘ What one does is so little compared to one’s ambitions for it.“

He hasn’t read reviews for many years, which seems odd for such a prolific reviewer. Why? „I spend two, three to five years writing a book. I know its failings. I know the few areas in which it’s succeeded. The only person who can’t read this book is me because I bring to it all the history, all the dead cats and slime and that Tuesday afternoon when you said ‚Fuck it‘, and you let the paragraph go.“

One reason he ought to read reviews of his books is that most of them are eulogies. Reviewing Banville’s 1997 novel The Untouchable in the Observer, George Steiner wrote: „Banville is the most intelligent and stylish novelist currently at work in English … The mien is austere and Victorian; the awareness, the ironic readings of the contemporary are razor-sharp.“

Has he ever stopped ventriloquising others and written in his own voice? „Only once. In The Book of Evidence“ – his 1989 Booker-shortlisted novel about a man who murders a servant while trying to steal a painting from a neighbour – „where the narrator says: ‚I have never really got used to being on this earth. Sometimes I think our presence here is due to a cosmic blunder, that we were meant for another planet altogether, with other arrangements, and other laws, and other, grimmer skies.‘ I believe this world is too gentle for us. We should have been in an iron world, not this one. I used to drive in to work at five o’clock in the evening looking at the sky, thinking ‚Who arranged this exquisite thing?‘ How I wasn’t killed, I don’t know. This world is terrible and savage but it’s absolutely exquisite and we don’t deserve it.“

In 2005, Banville won the Booker prize for The Sea, about an art historian returning to a seaside village where he spent a childhood holiday. The award was surprising, as Banville seemed to have queered his pitch. In 1981 he wrote to the Guardian waspishly requesting that that year’s Booker prize, for which he was „runner-up to the shortlist of contenders“, be given to him so that he could use the money to buy every copy of the longlisted books in Ireland and donate them to libraries, „thus ensuring that the books not only are bought but also read – surely a unique occurrence.“

Worse yet, he had – by his own admission – made powerful enemies earlier in 2005 with his New York Review of Books demolition of Ian McEwan’s novel Saturday, which he called „a dismayingly bad book“. „It looked like one novelist kicking another novelist, and that wasn’t what it was at all. As far as one can be disinsterested, I was reviewing it in a disinterested way. But, boy, have I made a lot of enemies.“

Among those enemies, he feared, was John Sutherland, Booker chairman in 2005. But, with the judges poised between The Sea and Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, Sutherland cast his deciding vote in favour of Banville. „Curious because he’d been furious with me for my review of McEwan.“ Then he bit the hand. „I blew the whole bloody thing by being michievious in an interview on BBC2 with Kirsty Wark.“ He said: „Whether The Sea is a successful work of art is not for me to say, but a work of art is what I set out to make. The kind of novels that I write very rarely win the Man Booker prize, which in general promotes good, middlebrow fiction.“

So does Ancient Light stand a chance of being shortlisted for the Booker? „I think they may as well call the whole thing off and give me the prize now!“ Banville has written a film adaptation of The Sea, which is to be directed by Stephen Brown and will star Ciarán Hinds. Like his prolific book reviewing, film writing is an enjoyable sideline from fiction. He has an as yet unfilmed screenplay on the life of his Irish revolutionary hero Roger Casement, which he wrote for director Neil Jordan. He wrote a script, based on a George Moore short story, for Glenn Close to play a 19th-century Dublin cross-dresser in last year’s film Albert Nobbs. Now he’s working with director Jonathan Kent on an Irish-set adaptation of Turgenev’s A Month in the Country.

„My ideal would be to be one of those hacks in a bungalow in the Hollywood Hills in the late 40s, and a producer with a cigar in his mouth says: ‚We need two scenes by 6 o’clock and they’d better be good, kid, or you’re off the movie.‘ I’d love to have worked like that.“ It would be an antidote to the solitary torture of being John Banville, maker of baroquely structured Nabokovian works of art. For similar reasons, no doubt, after The Sea, he devised the nom de plume Benjamin Black, whose crime novels today are more prominently displayed than Banville’s books at Dublin airport’s bookshops. Why did he create Black? „I love being a craftsman. I love writing reviews. I quite like being Benjamin Black. But being John Banville I absolutely hate.“ No wonder: it is Banville’s stated ambition to give his prose „the kind of denseness and thickness that poetry has“. „On a good day Banville can’t write more than 400 words, but they are all in more or less the right order. With Black it’s 10 times more.“

Being Black also gives him a break from being misconstrued as Banville, literary sage of the emotions. „I have this friend who has an incredibly complicated love life and she says: ‚Advise me, John.‘ I say: ‚I can’t. Just because I write about something doesn’t mean I know anything about it.‘ One of my models is Kafka, who said: ‚Never again psychology!‘ He’s right – artists are witnesses, we present the surface. As Nietzsche said, surfaces are where the real depth is. „

In Ancient Light the narrator says he doesn’t understand human motivation, his own least of all. „That’s true of all of us, isn’t it? Do you think you understand yourself?“ He maintains we get further from self-understanding as we get older. „I used to think age brings wisdom, but it only brings confusion. A friend of mine visited Beckett in his old folks‘ home in Paris and he said he was getting so old he was forgetting so many things. My friend sympathised and Beckett said: ‚No, no – it’s wonderful!‘ I know what he means: so much trivia gets wiped.

„It’s quite comic, the spectacle of one’s own creeping dissolution. Not so much the usual funny things of forgetting why you went upstairs, but actually to watch the physical stuff decay. It’s definitely comic. I hadn’t seen a profile photograph of myself for about 30 years until the other day. I thought: your hair’s going as well.“

Banville stands to go: „You have enough. You have the jokes, the arrogance and the sermon.“ I wanted more, I tell him. Over his shoulder he gives me a parting joke: „It’s no good – I can’t do humility.“

10 Remarkable Ways Meditation Helps Your Mind — PsyBlog

10 Remarkable Ways Meditation Helps Your Mind — PsyBlog.

Meditation is about way more than just relaxing.

In fact, if I listed the following mental benefits from a new pill or potion, you’d be rightly sceptical.

But all these flow from a simple activity which is completely free, involves no expensive equipment, chemicals, apps, books or other products.

I’ve also included my own very brief meditation instructions below to get you started.

But first, what are all these remarkable benefits?

1. Lasting emotional control

Meditation may make us feel calmer while we’re doing it, but do these benefits spill over into everyday life?

Desborders et al. (2012) scanned the brains of people taking part in an 8-week meditation program, before and after the course.

While they were scanned, participants looked at pictures designed to elicit positive, negative and neutral emotional responses.

After the meditation course, activation in the amygdala, the emotional centre of the brain, was reduced to all pictures.

This suggests that meditation can help provide lasting emotional control, even when you are not meditating.

2. Cultivate compassion

Meditation has long been thought to help people be more virtuous and compassionate. Now this has been put to scientific test.

In one study participants who had been meditating were given an undercover test of their compassion (Condon et al., 2013).

They were sat in a staged waiting area with two actors when another actor entered on crutches, pretending to be in great pain. The two actors sat next to the participants both ignored the person who was in pain, sending the unconscious signal not to intervene.

Those who had been meditating, though, were 50% more likely to help the person in pain.

One of the study’s authors, David DeSteno, said:

“The truly surprising aspect of this finding is that meditation made people willing to act virtuous–to help another who was suffering–even in the face of a norm not to do so.”

3. Change brain structures

Meditation is such a powerful technique that, after only 8 weeks, the brain’s structure changes.

To show these effects, images of 16 people’s brains were taken before and after they took a meditation course (Hölzel et al., 2011).

Compared with a control group, grey-matter density in the hippocampus–an area associated with learning and memory–was increased.

The study’s lead author, Britta Hölzel, said:

“It is fascinating to see the brain’s plasticity and that, by practicing meditation, we can play an active role in changing the brain and can increase our well-being and quality of life.”

4. Reduce pain

One of the benefits of changes to the brain’s structure is that regular meditators experience less pain.

Grant et al. (2010) applied a heated plate to the calves of meditators and non-meditators. The meditators had lower pain sensitivity.

Joshua Grant explained:

“Through training, Zen meditators appear to thicken certain areas of their cortex and this appears to be underlie their lower sensitivity to pain.”

5. Accelerate cognition

How would you like your brain to work faster?

Zeidan et al. (2010) found significant benefits for novice meditators from only 80 minutes of meditation over 4 days.

Despite their very brief period of practice—and compared with a control group who listened to an audiobook of Tolkein’s The Hobbit—meditators improved on measures of working memory, executive functioning and visuo-spatial processing.

The authors conclude:

“…that four days of meditation training can enhance the ability to sustain attention; benefits that have previously been reported with long-term meditators.”

Improvements seen on the measures ranged from 15% to over 50%.

The full article: Cognition Accelerated by Just 4 x 20 Minutes Meditation

6. Meditate to create

The right type of meditation can help solve some creative problems.

A study by Colzato et al. (2012) had participants take a classic creativity task: think up as many uses as you can for a brick.

Those using an ‘open monitoring’ method of meditation came up with the most ideas.

This method uses focusing on the breath to set the mind free.

7. Sharpen concentration

At its heart, meditation is all about learning to concentrate, to have greater control over the spotlight of attention.

An increasing body of studies now underline the benefits of meditation for attention.

For example, Jha et al. 2007 sent 17 people who had not practised meditation before on an 8-week training course in mindfulness-based stress reduction, a type of meditation.

These 17 participants were then compared with a further 17 from a control group on a series of attentional measures. The results showed that those who had received training were better at focusing their attention than the control group.

The full article: How Meditation Improves Attention

8. Improve multitasking at work

Since meditation benefits different aspects of cognition, it should also improve work performance.

That’s what Levy et al. (2012) tested by giving groups of human resource managers tests of their multitasking abilities.

Those who practised meditation performed better on standard office tasks–like answering phones, writing email and so on–than those who had not been meditating.

Meditating managers were better able to stay on task and also experienced less stress as a result.

9. Reduce anxiety

Meditation is an exercise often recommended for those experiencing anxiety.

To pick just one of many recent studies, Zeidan et al. (2013) found that four 20-minute meditation classes were enough to reduce anxiety by up to 39%.

More about anxiety: 8 Fascinating Facts About Anxiety

10 Fight depression

A central symptom of depression is rumination: when depressing thoughts roll around and around in the mind.

Unfortunately you can’t just tell a depressed person to stop thinking depressing thoughts; it’s pointless. That’s because treating the symptoms of depression is partly about taking control of the person’s attention.

One method that can help with this is mindfulness meditation. Mindfulness is all about living in the moment, rather than focusing on past regrets or future worries.

A recent review of 39 studies on mindfulness has found that it can be beneficial in treating depression (Hofmann et al., 2010).

Read on: Depression: 10 Fascinating Insights into a Misunderstood Condition

Beginner’s guide to meditation

Since it is so beneficial, here is a quick primer on how to meditate.

The names and techniques of meditation are many and varied, but the fundamentals are much the same:

1. Relax the body and the mind

This can be done through body posture, mental imagery, mantras, music, progressive muscle relaxation, any old trick that works. Take your pick.

This step is relatively easy as most of us have some experience of relaxing, even if we don’t get much opportunity.

2. Be mindful

It’s a bit cryptic this one but it means something like this: don’t pass judgement on your thoughts, let them come and go as they will (and boy will they come and go!). When your mind wanders, try to nudge your attention back to its primary aim.

It turns out this is quite difficult because we’re used to mentally travelling backwards and forwards while making judgements on everything (e.g. worrying, dreading, anticipating, regretting etc.).

The key is to notice, in a detached way, what’s happening, but not to get involved with it. This way of thinking often doesn’t come that naturally.

3. Concentrate on something

Often meditators concentrate on their breath, the feel of it going in and out, but it could be anything: your feet, a potato, a stone.

The breath is handy because we carry it around with us. Whatever it is, though, try to focus all your attention onto it.

When your attention wavers, and it will almost immediately, gently bring it back. Don’t chide yourself, be compassionate to yourself.

The act of concentrating on one thing is surprisingly difficult: you will feel the mental burn almost immediately. Experienced practitioners say this eases with practice.

4. Concentrate on nothing

Most say this can’t be achieved without a lot of practice, so I’ll say no more about it here. Master the basics first.

Explore

This is just a quick introduction but does give you enough to get started. It’s important not to get too caught up in techniques but to remember the main goal: exercising attention by relaxing and focusing on something.

Try these things out first, see what happens, then explore further.