It comes naturally to most of us to think of music as therapeutic. Almost all of us are, without training, DJs of our own souls, deft at selecting pieces of music that will enhance or alter our current moods for the better. Yet few of us would think of turning to the visual arts for this kind of help. Few of us involve paintings or sculptures in our emotional lives. We don’t have playlists of favourite images on our phones. We don’t assemble our own private galleries on our computers. The cost and prestige of art typically draws us back from such steps. The way the establishment presents art to us doesn’t invite us to bring ourselves into contact with works.

In the solemn galleries of museums, which is still where most of us pick up cues about how to behave around art, many of us are – in our hearts – a little lost (the gift shop is more helpful; it may be embarrassingly easier to have a fruitful time with the postcard than the original). We look at the caption and dutifully learn some key dates, the provenance and perhaps an explanation of an allegory. But could this really matter to me? What should art really be for?

The second question has long felt either vulgar and impatient or else simply unanswerable. This is dangerous. If art deserves its enormous prestige (and I think it does), then it should be able to state its purpose in relatively simple terms. I believe art is ultimately a therapeutic medium, just like music. It, too, is a vehicle through which we can do such things as recover hope, dignify suffering, develop empathy, laugh, wonder, nurture a sense of communion with others and regain a sense of justice and political idealism.

But for it to do any of these things for us, we need to approach art in the right sort of way. It needs to be framed not principally according to the criteria of art history (however interesting those can be), but according to a psychological method that invites us to align our deeper selves with artworks. What does a psychological therapeutic way of reading art look like? A selection of works suggests the way.

Hope

Bridge Over a Pond of Water Lilies (1899) by Claude Monet (above)

Monet’s painting is one of the most popular works in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This is worrying to many people of taste and sophistication, who take a taste for „prettiness“ as a symptom of sentimentality, even stupidity.

The worry might be that the fondness for this kind of art is a delusion: those who love pretty gardens are in danger of forgetting the actual conditions of life, which include war, disease and political error and immorality. Audiences need art constantly to remind them of this kind of material, sophisticated types will propose, or they might end up deluded as to what life is actually like.

But this is to locate the problem in completely the wrong place. For most of us, the greatest risk we face is not complacency; few of us are likely to forget the evils of existence. The real risk is that we are going to fall into fury, depression and despair; the danger is that we will lose all hope in the human project.

It is this kind of despair that art is well suited to correct and that explains the well-founded popular enthusiasm for prettiness. Flowers in spring, blue skies, children running on the beach … these are the visual symbols of hope. Cheerfulness is an achievement and hope is something to celebrate.

Empathy

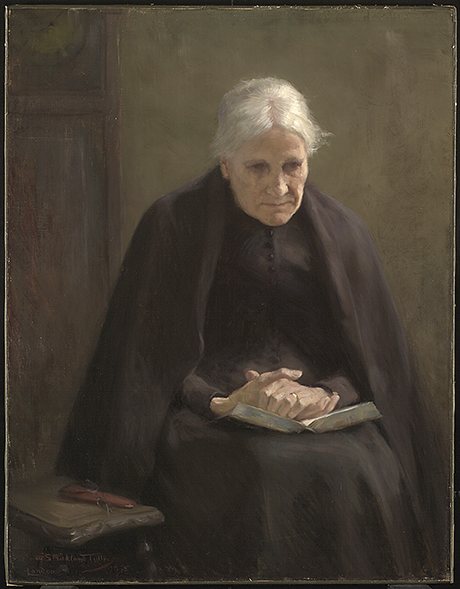

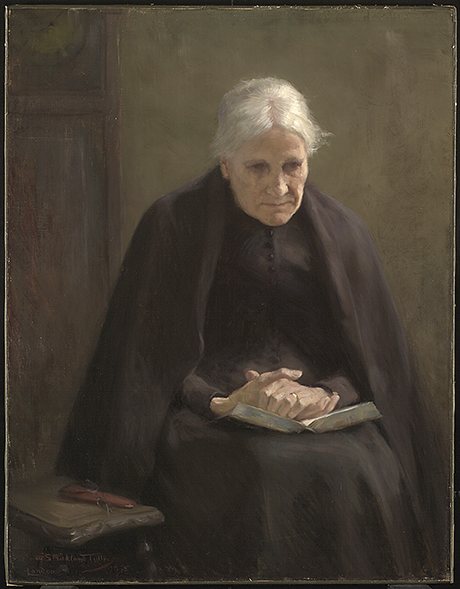

The Twilight of Life (1894) by Sydney Tully

Photograph: Art Gallery Of Ontario It’s hard to take much of an interest in other people, especially perhaps elderly people. In Tully’s portrait, an elderly woman sits stooped and thoughtful against a stark background. We’re being encouraged to look for longer than we normally would. She used to be strong and decisive. She had lovers once; she carefully set out with a quiet thrill in the evening.

Photograph: Art Gallery Of Ontario It’s hard to take much of an interest in other people, especially perhaps elderly people. In Tully’s portrait, an elderly woman sits stooped and thoughtful against a stark background. We’re being encouraged to look for longer than we normally would. She used to be strong and decisive. She had lovers once; she carefully set out with a quiet thrill in the evening.

Now, she’s hard to love and maybe she knows this. She gets irritated, she withdraws. But she needs other people to care for her. Anyone can end up in her position. And there are moments when a lot of people – at whatever stage of life – are a bit hard to admire or like. Love is often linked to admiration: we love because we find another person exciting and sweet. But there’s another aspect to love in which we are moved by the need of the other, by generosity.

Tully is generous to her sitter. The painter looks with care into her face and wonders who she might really be.

Care

14th-century Venetian glass

Photograph: Getty Images/DeAgostini The glass workshops of Venice became famous in the medieval period for producing the most elaborate, delicate, transparent glassware mankind had ever known. Most of the time, we have to be strong. We must not show our fragility. We’ve known this since the playground. There is always a fragile bit of us, but we keep it very hidden. Yet Venetian glass doesn’t apologise for its weakness. It admits its delicacy; it makes the world understand it could easily be damaged.

Photograph: Getty Images/DeAgostini The glass workshops of Venice became famous in the medieval period for producing the most elaborate, delicate, transparent glassware mankind had ever known. Most of the time, we have to be strong. We must not show our fragility. We’ve known this since the playground. There is always a fragile bit of us, but we keep it very hidden. Yet Venetian glass doesn’t apologise for its weakness. It admits its delicacy; it makes the world understand it could easily be damaged.

The glass is not fragile because of a deficiency, or by mistake. It’s not as if its maker was trying to make it tough and hardy and then – stupidly – ended up with something a child could snap. It is fragile and easily harmed as the consequence of its search for refinement and its desire to welcome sunlight and candlelight into its depths. Glass can achieve wonderful effects, but the price is fragility. It is the duty of civilisation to allow the more delicate forms of human activity to thrive; to create environments where it is OK to be fragile. It’s obvious the glass could be smashed, so it makes you use your fingers tenderly. It is a moral tale about gentleness, told by means of a drinking vessel. This is training for the more important moments in life when moderation will make a real difference to other people. Being mature means being aware of the effect of one’s strength on others. CEOs please take note.

Sorrow

Fernando Pessoa (2007-08) by Richard Serra

Photograph: David Levene for the Guardian We’re often intensely lonely in our suffering. In an upbeat world that worships success, our miseries feel shameful. We’re not only sad, we’re sad at being the only ones that seem to be so. We can’t remove suffering from life, but we can learn to suffer more successfully – that is, with less of a sense of persecution or an impression that we have unfairly been singled out for punishment. Fernando Pessoa is a beautifully dark monumental work by Richard Serra, named after a Portuguese poet with a turn for lamentation („Oh salty sea/ how much of your salt is tears from Portugal“).

Photograph: David Levene for the Guardian We’re often intensely lonely in our suffering. In an upbeat world that worships success, our miseries feel shameful. We’re not only sad, we’re sad at being the only ones that seem to be so. We can’t remove suffering from life, but we can learn to suffer more successfully – that is, with less of a sense of persecution or an impression that we have unfairly been singled out for punishment. Fernando Pessoa is a beautifully dark monumental work by Richard Serra, named after a Portuguese poet with a turn for lamentation („Oh salty sea/ how much of your salt is tears from Portugal“).

The work does not deny our sorrows, it does not tell us to cheer up or point us in a brighter direction. The large scale and monumental character of this sombre sculpture declare the normality and universality of grief. It is confident that we will recognise and respond to the legitimate place of solemn emotions in an ordinary life.

Rather than leaving us alone with our darker moods, the work proclaims them as central features of life. In its stark gravity, like many of the greatest works of art, it creates a dignified home for sorrow.

Work

At the Linen Closet (1663) by Pieter de Hooch

www.bridgemanart.com In this modest domestic scene by the 17th-century Dutch genre painter Pieter de Hooch, we see a couple of women busy with a household task. There are no soldiers, kings, martyrs or divine figures in sight; this is ordinary life as we know it to this day.

www.bridgemanart.com In this modest domestic scene by the 17th-century Dutch genre painter Pieter de Hooch, we see a couple of women busy with a household task. There are no soldiers, kings, martyrs or divine figures in sight; this is ordinary life as we know it to this day.

It can be hard to see beauty and interest in the things we have to do every day and in the environments where we live. We have jobs to go to, bills to pay, homes to clean and we deeply resent the demands they make on us. The linen closet itself could easily be resented. It is an embodiment of what could be seen as boring, banal, even unsexy.

But the picture moves us because we recognise the truth of its message. If only, like De Hooch, we knew how to recognise the value of ordinary routine, many of our burdens would be lifted. It gives voice to the right attitude: the big themes of life – the search for prosperity, happiness, good relationships – are always grounded in the way we approach little things. The statue above the door is a clue. It represents money, love, status, vitality, adventure. Taking care of the linen is not opposed to these grander hopes. It is, rather, the way to them. We can learn to see the allure of those who look after it, ourselves included.

That so many people revere this painting is hopeful; it signals that we know, deep down, that De Hooch is on to something important.

Appreciation

An Idyll: Daphnis and Chloe (1500-01) by Nicola Pisano

Photograph: Copyright The Wallace Collection In his Daphnis and Chloe, Pisano evokes the beginnings of love, a moment when the sweetness and grace of the other is intensely present to us. Daphnis regards Chloe as so precious, he hardly dares to touch her. All his devotion, his honour and his hopes for the future are vivid to him. He wants to deserve her; he does not know if she will love him and this doubt intensifies his delicacy. In his eyes, she absolutely cannot be taken for granted. Seen by someone in a long-term relationship, when habit has made the other completely familiar, this image comes across as particularly necessary, because of its power to return us to a forgotten sense of gratitude and wonder.

Photograph: Copyright The Wallace Collection In his Daphnis and Chloe, Pisano evokes the beginnings of love, a moment when the sweetness and grace of the other is intensely present to us. Daphnis regards Chloe as so precious, he hardly dares to touch her. All his devotion, his honour and his hopes for the future are vivid to him. He wants to deserve her; he does not know if she will love him and this doubt intensifies his delicacy. In his eyes, she absolutely cannot be taken for granted. Seen by someone in a long-term relationship, when habit has made the other completely familiar, this image comes across as particularly necessary, because of its power to return us to a forgotten sense of gratitude and wonder.

Relationships

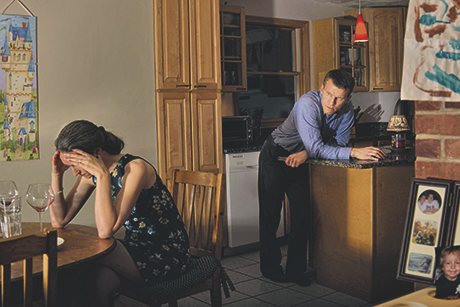

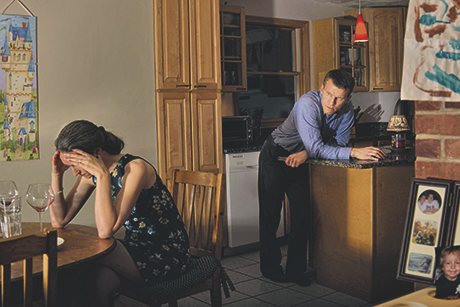

The Agony in the Kitchen (2012) by Jessica Todd Harper

Photograph: Copyright the artist We’re surrounded by images of what relationships are like – many of which are deeply deceptive and harmful to our own chances of being contented with another person. People seldom talk with complete sincerity about what is happening inside their relationships.

Photograph: Copyright the artist We’re surrounded by images of what relationships are like – many of which are deeply deceptive and harmful to our own chances of being contented with another person. People seldom talk with complete sincerity about what is happening inside their relationships.

Behind the silence lies a need to maintain face about one’s progress through one of the most significant challenges of adult life: a capacity to succeed at being happy with someone else.

We need works of art that can show us that our troubles are both sad and normal. We don’t need the diametric opposite of the saccharine images of Hollywood. Extremes of domestic violence are rare. But day‑to‑day struggles are universal, though often unrepresented and unseen.

In Jessica Todd Harper’s image, a couple has perhaps been planning to have a nice evening yet it has now all gone wrong. One person is feeling incensed; the other is perhaps crying.

Importantly, however, these could be nice people. We are not to condemn them. They are likable, but in the grip of a genuinely difficult problem. And you have been there yourself.

Art can function as a private repository for truths that are too peculiar and too unacceptable to be shared with people we know.

Consumerism

Cookmaid with Still Life of Vegetables and Fruit (1620‑05) by Nathaniel Bacon

Photograph: Tate The idea of consumerism as evil is a scourge with which to beat the modern world. Yet at its best consumerism is founded on love of the fruits of the earth, delight in human ingenuity and due appreciation of the vast achievements of organised effort and trade. This painting takes us to a time when abundance was new and not to be taken for granted.

Photograph: Tate The idea of consumerism as evil is a scourge with which to beat the modern world. Yet at its best consumerism is founded on love of the fruits of the earth, delight in human ingenuity and due appreciation of the vast achievements of organised effort and trade. This painting takes us to a time when abundance was new and not to be taken for granted.

We are so afraid of greed that we forget how honourable the love of material things can be. In 1620, homage could be paid to the nobility of work and commerce, something that boredom and guilt make less accessible to us today. Perhaps we can learn from this picture. A good response to consumerism might not be to live without melons and grapes, but to appreciate what really needs to go into providing them.