John Warner stellt mit Blick auf ChatGPT die Frage, was am aktuellen Schreibunterricht eigentlich erhaltenswert ist und was wir getrost über Bord werfen können. Beitrag in Deutsch und Englisch (post in German and English).

Kategorie: Language

William Blake’s Most Beautiful Letter: A Timeless Defense of the Imagination and the Creative Spirit

“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way… As a man is, so he sees.”

Quelle: William Blake’s Most Beautiful Letter: A Timeless Defense of the Imagination and the Creative Spirit

Maria Popova „Figuring“

The author of “Figuring” (and the brain behind the Brain Pickings website) likes how children’s books speak “a language of absolute sincerity, so deliciously countercultural in our age of cynicism.”

What books are on your nightstand?

I don’t have a nightstand per se — my bedroom is rather ascetic, with only a bed nestled between the constellation-painted walls. I do tend to keep a rotating selection of longtime favorites near or in it, to dip into before sleep — “The Little Prince” (which I reread at least once a year every year, and somehow find new wisdom and pertinence to whatever I am going through at the moment), “The Lives of the Heart,” by Jane Hirshfield, “Hope in the Dark,” by Rebecca Solnit, Thoreau’s diaries, “How the Universe Got Its Spots,” by Janna Levin. Of the piles that inevitably accumulate in every room of my house, friends’ books I have recently read and loved tower nearest the bed — part synonym and part antonym to the lovely Japanese concept of tsundoku, the guilt-pile of books acquired with the intention of reading but left unread. Currently among my anti-tsundoku: “Time Travel,” by James Gleick, “Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine,” by Alan Lightman, “Little Panic,” by Amanda Stern, “Inheritance,” by Dani Shapiro, and an exhibition catalog — which, in her case, is part poetry and part philosophy — by Ann Hamilton.

What’s the last great book you read?

I read multiple books each week and have no qualms about abandoning what fails to captivate me, so I tend to love just about everything I finish. At this particular moment, I am completely smitten with Jill Lepore’s history of America — what a rare masterwork of rigorous scholarship with a poetic sensibility — but I am barely a quarter through, so I’d be cheating if I counted it as read.

I only recently discovered, and absolutely loved, “The Living Mountain,” by the Scottish mountaineer and poet Nan Shepherd — part memoir, part field notebook, part lyrical meditation on nature and our relationship with it, evocative of Rachel Carson and Henry Beston and John Muir. Shepherd composed it sometime around World War II, but kept it in a drawer for nearly four decades, until the final years of her life. Decades after her death, her work — much of it by then out of print — was rediscovered and championed by Robert Macfarlane, a splendid nature writer himself.

Are there any classic novels that you only recently read for the first time?

Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.” I am filled with disbelief bordering on shame that I went this long without it. A book that gives the English language back to itself and your conscience back to itself.

Do your blog posts grow out of whatever you happen to be reading at the time? Or do you pick books specifically with Brain Pickings in mind?

- Unlock more free articles.

I don’t see my website as a separate entity or any sort of media outlet — it is the record and reflection of my inner life, my discourse with ideas and questions through literature, my extended marginalia. It is a “blog” in the proper sense — a “web log,” part commonplace book and part ledger of a life. Nothing on it is composed for an audience. I write about what I read, and I read to process what I dwell in, mentally and emotionally. The wondrous thing about being human — the beauty and banality of it — is that we all tend to dwell in the same handful of elemental struggles, joys and sorrows, which is why a book one person writes may help another process her own life a century later, and why a “blog” by a solitary stranger may speak to many other solitary dwellers across time and space.

What moves you most in a work of literature?

Rhythm, texture, splendor of sentiment in language, unsentimental soulfulness.

Which genres do you especially enjoy reading? And which do you avoid?

I read mostly nonfiction and poetry. But I also don’t believe in genre as a defining feature of substance. Ursula K. Le Guin’s fantasy is animated by rich moral philosophy. Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel “Are You My Mother?” is replete with more insight into the human psyche than most books in the psychology section of the bookstore. Great children’s books speak to the most elemental truths of existence, and speak in the language of children — a language of absolute sincerity, so deliciously countercultural in our age of cynicism.

How do you organize your books?

My children’s book library is organized by color, everything else by subject and substance first — science, poetry, biographies and autobiographies, diaries and letters, etc. — then within each section, by color. I break the color system for multiple books by the same author on related subjects — amid several Oliver Sacks volumes huddled together, “Hallucinations” beams from the solemn science shelf with its cheerful seizure of cyan.

What’s the best book you’ve ever received as a gift?

My good friend and collaborator Claudia Bedrick, founder of the visionary Enchanted Lion Books, gave me a trilingual pop-up book titled “Little Tree,” by the Japanese graphic designer and book artist Katsumi Komagata — a subtle, stunning meditation on mortality through the life-cycle of a single tree, inspired by a young child struggling to make sense of a beloved father’s death — one of the artist’s close friends. I have a deep love of trees — they have been among my wisest teachers — and recently returned to this book while spending time with one of my own dear friends in the final weeks of her life.

Who is your favorite fictional hero or heroine? Your favorite antihero or villain?

Orlando. It is hard not to fall in love with a beautiful, brilliant creature who changes genders while galloping across three centuries on a pair of “the shapeliest legs” in the land. It is hard not to fall in love with Virginia Woolf’s love for Vita Sackville-West, on whom Orlando is modeled and to whom the book is dedicated. Vita’s son later described the novel as “the longest and most charming love letter in literature.”

In a sense, Orlando is also an antihero in the drama of Woolf’s oppressive heteronormative society — a subversion, a counterpoint to convention, a sentinel of the resistance. A month after the book’s publication, the novelist Radclyffe Hall was tried for obscenity — the same half-coded charge of homosexuality for which Oscar Wilde had been imprisoned a generation earlier — and all printed copies of her lesbian novel “The Well of Loneliness” were destroyed by court order. In response to the trial, Woolf and E. M. Forster wrote in a joint letter of protest: “Writers produce literature, and they cannot produce great literature until they have free minds. The free mind has access to all knowledge and speculation of its age, and nothing cramps it like a taboo.”

What kind of reader were you as a child? Which childhood books and authors stick with you most?

I don’t recall being much of a natural reader early on, but my paternal grandmother made me one. She read me old European fairy tales — Hans Christian Andersen, the uncandied Brothers Grimm. (In the communist Bulgaria of my childhood, the classics of American children’s literature were barred by the Iron Curtain.) I especially loved “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” long before I could fully appreciate the allegorical genius of a brilliant logician. I was awed by my grandmother’s enormous library and was particularly enchanted by the encyclopedias, the way you could pull one out and open to a random page and learn about something thrilling you didn’t even know existed. It is an experience we rarely have anymore in a culture where pointed search has eclipsed serendipitous discovery, leading us to find more and more of what we are already interested in. In a sense, this encyclopedic enchantment and the delight of unbidden discovery have stayed with me and become the backbone of Brain Pickings.

What’s the most interesting thing you learned from a book recently?

From the fantastic new biography of Benjamin Rush by Stephen Fried — my first and foremost writing mentor, whose research intern I was what seems like a lifetime ago, and was even paid two subway tokens per week for the pleasure — I learned that we owe to this “footnoted founder” our formative understanding of mental illness and the then-radical notion that mentally ill people are still people. A century before Nellie Bly’s paradigm-shifting exposé “Ten Days in a Madhouse,” at a time when mental asylum patients were chained to the floor until they “improved,” Rush insisted that their humanity and dignity must be honored in treatment, and pioneered forms of psychiatric care closely resembling the modern. This radical, largehearted reformer was decades, perhaps centuries ahead of his time along so many axes of progress: He became the nation’s pre-eminent champion of public health and public schooling, founded the country’s first rural college, railed against racism, helped African-American clergymen establish two of the nation’s first churches for black congregations, and pushed to extend education to women, African-Americans and non-English-speaking immigrants. (He also penned the most devastating and delightful rant against materialism, condemning America as “a bebanked, and a bewhiskied & a bedollared nation.” I wonder how he would have framed the unfathomable notion that his nation would one day be governed by a billionaire who deals in golf courses, stars in his own reality TV show and bankrolls the business of hate.)

If you could require the president to read one book, what would it be?

I am resisting the cheap impulse to simply say, “Any.” Instead, I’d say Hannah Arendt’s “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” but there is the obvious risk that he might take it for an instructional manual.

Perhaps the safest thing for everyone would be to give the man some poetry — it has a singular way of slipping through the backdoor of the psyche to anneal truth and open even the most fisted heart, “to awaken sleepers by other means than shock,” as the poet Denise Levertov put it. I’d say “Crave Radiance,” by Elizabeth Alexander — one of our finest living poets — but I doubt the fact that she was Barack Obama’s inauguration poet would go over well with the current administration.

Any book by Jane Hirshfield — a splendid poet and an ordained Buddhist — would probably do more good in this country, in the White House and in every home, than all the political op-eds and polemics combined.

You’re organizing a literary dinner party. Which three writers, dead or alive, do you invite?

Rachel Carson, Susan Sontag, Margaret Fuller. It could go one of two ways: intoxicating intellectual repartee — the fiercely opinionated Sontag and Fuller would either love or loathe one another, and Carson would sit in unassuming quietude, speaking only rarely and with the perfect, perfectly formulated sentiment — or literary speed dating for queer women. I, for one, am half-infatuated with all three.

How do you decide what to read next? Is it reviews, word-of-mouth, books by friends, books for research? Does it depend on mood or do you plot in advance?

I often say that literature is the original internet — every allusion, footnote and reference is a hyperlink to another text. Nearly all books I read enter my life through the gateway of other books, which explains why, over the nearly 13-year span of Brain Pickings, my writing has plunged deeper and deeper into the past — this analog web only extends backward in time, for a book can only reference texts previously published. It’s a great antidote to the presentism bias that envelops us, in which we mistake the latest and the loudest — the flotsam of opinion atop social media streams — for the most important, most insightful, most relevant. Right around Ferguson, I discovered through a passing mention in an out-of-print collection of Margaret Mead’s Redbook advice columns her 1970 conversation with James Baldwin, in which they discuss race, gender, identity, democracy, morality, the immigrant experience and a great many other topics of acute relevance today, with tenfold the dignity and depth of insight than our current modes of cultural discourse afford.

What do you plan to read next?

I recently discovered Jenny Uglow’s 2002 biography of the Lunar Men — a small group of freethinking intellectuals, whose members are responsible for the development of the steam engine and a cascade of other advances in science. Somehow, I had completely missed it in my research, even though members of the Lunar Men flit in and out of “Figuring.” The more you read, the more you miss.

Language like poppies in Ali Smith’s Autumn — Sentence first

Autumn (2016), like all of Ali Smith’s novels (I’m guessing – I’ve only read a few so far), is a delight in linguistic and other ways. This post features a few excerpts that focus on language in one way or another. The main character, Elisabeth, is visiting her old friend Daniel in a care home. […]

Language like poppies in Ali Smith’s Autumn — Sentence first

Saul Bellow’s Spectacular Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech on How Art and Literature Ennoble the Human Spirit | Brain Pickings

“Only art penetrates … the seeming realities of this world. There is another reality, the genuine one, which we lose sight of. This other reality is always sending us hints, which without art, we can’t receive.”

In a 1966 interview, Saul Bellow (June 10, 1915–April 5, 2005) articulated the seed of what would blossom into a central concern of his life, and of our culture: “Art has something to do with the achievement of stillness in the midst of chaos. A stillness which characterizes prayer, too, in the eye of the storm… Art has something to do with an arrest of attention in the midst of distraction.” A quarter century later — already an elder with a Pulitzer Prize, a National Medal of Arts, and a Nobel Prize under his belt — Bellow would come to explore this duality more deliberately in his stirring essay on how artists and writers save us from the “moronic inferno” of distraction.

In a 1966 interview, Saul Bellow (June 10, 1915–April 5, 2005) articulated the seed of what would blossom into a central concern of his life, and of our culture: “Art has something to do with the achievement of stillness in the midst of chaos. A stillness which characterizes prayer, too, in the eye of the storm… Art has something to do with an arrest of attention in the midst of distraction.” A quarter century later — already an elder with a Pulitzer Prize, a National Medal of Arts, and a Nobel Prize under his belt — Bellow would come to explore this duality more deliberately in his stirring essay on how artists and writers save us from the “moronic inferno” of distraction.

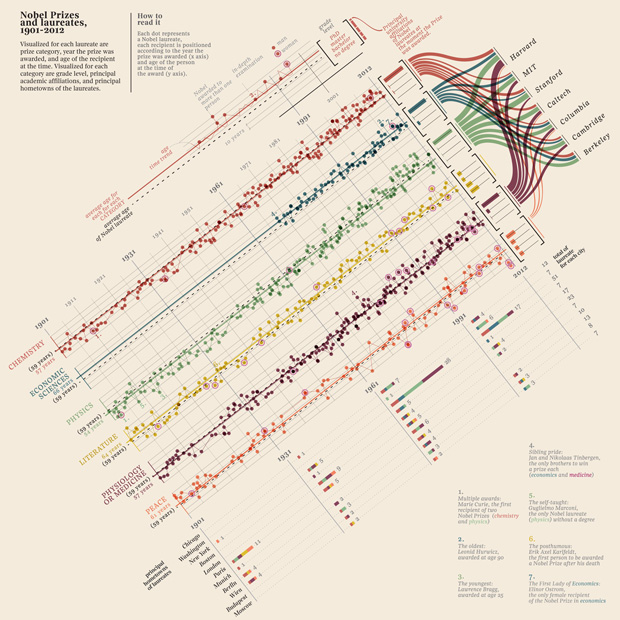

But nowhere does the celebrated author address his views on the artist’s task more directly than in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize awarded to him in 1976 “for the human understanding and subtle analysis of contemporary culture that are combined in his work.” Eventually published in Nobel Lectures in Literature, 1968–1980 (public library), it remains one of the greatest public addresses of all time.

Reflecting on the death of the notion of “character” in literature, Bellow writes:

I am interested here in the question of the artist’s priorities. Is it necessary, or good, that he should begin with historical analysis, with ideas or systems?

[…]

I myself am tired of obsolete notions and of mummies of all kinds but I never tire of reading the master novelists. And what is one to do about the characters in their books? Is it necessary to discontinue the investigation of character? Can anything so vivid in them now be utterly dead? … Can we accept the account of those conditions we are so “authoritatively” given? I suggest that it is not in the intrinsic interest of human beings but in these ideas and accounts that the problem lies.

With an almost Buddhist attitude as applicable to literature as it is to life itself, Bellow adds:

To find the source of trouble we must look into our own heads.

He admonishes against taking on faith any death knell rung by our culture’s so-called experts — lest we forget, Frank Lloyd Wright put it best when he quipped that “an expert is a man who has stopped thinking because ‘he knows’” — and in a sentiment that renders just as laughable the modern death knell for the novel, he writes:

The fact that the death notice of character “has been signed by most serious essayists” means only that another group of mummies, the most respectable leaders of the intellectual community, has laid down the law. It amuses me that these serious essayists should be allowed to sign the death notices of literary forms. Should art follow culture? Something has gone wrong.

Many decades before Tom Wolfe’s spectacular commencement address admonishing against the tyranny of the pseudo-intellectual, Bellow adds:

We must not make bosses of our intellectuals. And we do them no good by letting them run the arts. Should they, when they read novels, find nothing in them but the endorsement of their own opinions? Are we here on earth to play such games?

Once again, Bellow reminds us that the anxieties and paranoias which every generation sees as singular to its era are anything but — 1976 sounds an awful lot like today:

The condition of human beings has perhaps never been more difficult to define…

Every year we see scores of books and articles which tell [people] what a state they are in — which make intelligent or simpleminded or extravagant or lurid or demented statements. All reflect the crises we are in while telling us what we must do about them; these analysts are produced by the very disorder and confusion they prescribe for.

[…]

In private life, disorder or near-panic. In families — for husbands, wives, parents, children — confusion; in civic behavior, in personal loyalties, in sexual practices (I will not recite the whole list; we are tired of hearing it) — further confusion. And with this private disorder goes public bewilderment.

[…]

It is with these facts that knock us to the ground that we try to live… There is no simple choice between the children of light and the children of darkness… But I have made my point; we stand open to all anxieties. The decline and fall of everything is our daily dread, we are agitated in private life and tormented by public questions.

Let me interject here with a necessary caveat: Despite the Swedish Academy’s brief to celebrate the value of literature and the arts in ennobling the human spirit, a great many Nobel Prize acceptance speeches bear the distinct flavor of Grumpy Old Man. This is a natural, if hardly excusable, product of the fact that the Nobel Prize has a long history of being granted primarily to old white men, not to mention it was established by a particularly grumpy one — a fact increasingly glaring and uncomfortable even for those of us dedicated to preserving the wisdom of our cultural and civilizational elders. How exasperating that such extraordinary writers as Susan Sontag, Chinua Achebe, and Maya Angelou died without a Nobel Prize.

And perhaps the sample pool is too small to draw scientifically valid conclusions, but there is palpable anecdotal evidence that when a writer like Albert Camus, the youngest laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature, or Pearl S. Buck, the second youngest laureate and the youngest woman to receive the coveted accolade, takes the stage at the Swedish Academy, there is a decidedly different ratio of grumpiness to gladness in their speech, of embitterment to emboldening faith in the human spirit. (cf. Hemingway’s.)

And now back to Grumpy Old Man Bellow, who is beneath grumpiness — or else, after all, he wouldn’t be here — a staunch champion of the power of art to elevate and enlarge the human spirit. Against this backdrop of dread and ruin, amid our growing spiritual hunger for quietude, he asks:

Art and literature — what of them? … We are still able to think, to discriminate, and to feel. The purer, subtler, higher activities have not succumbed to fury or to nonsense. Not yet. Books continue to be written and read. It may be more difficult to reach the whirling mind of a modern reader but it is possible to cut through the noise and reach the quiet zone. In the quiet zone we may find that he is devoutly waiting for us. When complications increase, the desire for essentials increases too. The unending cycle of crises that began with the First World War has formed a kind of person, one who has livd through terrible, strange things, and in whom there is an observable shrinkage of prejudices, a casting off of disappointing ideologies, an ability to live with many kinds of madness, an immense desire for certain durable human goods — truth, for instance, or freedom, or wisdom.

With an eye to Time Regained, the penultimate volume of Proust’s universally beloved seven-part novel In Search of Lost Time, Bellow considers the singular role of art in the human experience:

Only art penetrates what pride, passion, intelligence and habit erect on all sides — the seeming realities of this world. There is another reality, the genuine one, which we lose sight of. This other reality is always sending us hints, which without art, we can’t receive. Proust calls these hints our “true impressions.” The true impressions, our persistent intuitions, will, without art, be hidden from us and we will be left with nothing but a “terminology for practical ends which we falsely call life.”

Returning to the role of intellectuals in perpetuating such a quasi-reality of practical ends, Bellow considers the task of the writer and artist to reawaken our “true impressions”:

There is in the intellectual community a sizable inventory of attitudes that have become respectable — notions about society, human nature, class, politics, sex, about mind, about the physical universe, the evolution of life. Few writers, even among the best, have taken the trouble to re-examine these attitudes and orthodoxies… Literature has for nearly a century used the same stock of ideas, myths, strategies … maintaining all the usual things about mass society, dehumanization and the rest. How weary we are of them. How poorly the represent us. The pictures they offer no more resemble us than we resemble the reconstructed reptiles and other monsters in a museum of paleontology. We are much more limber, versatile, bette articulated, there is much more to us, we all feel it.

Bellow peers into the future of humanity, in the shaping of which we are all implicated — perhaps even more so today, when we are tenfold more interconnected and our fates more intertwined, than at the time of his speech:

Mankind [is] determining, in confusion and obscurity, whether it will endure or go under. The whole species — everybody — has gotten into the act. At such a time it is essential to lighten ourselves, to dump encumbrances, including the encumbrances of education and all organized platitudes, to make judgments of our own, to perform acts of our own… We must hunt for that under the wreckage of many systems. The failure of those systems may bring a blessed and necessary release from formulations, from an over-defined and misleading consciousness. With increasing frequency I dismiss as merely respectable opinions I have long held — or thought I held — and try to discern what I have really lived by, and what others live by.

In a sentiment that calls to mind psychoanalyst Adam Phillips’s magnificent meditation on the necessary excesses of our inner lives, Bellow adds:

Our very vices, our mutilations, show how rich we are in thought and culture. How much we know. How much we even feel. The struggle that convulses us makes us want to simplify, to reconsider, to eliminate the tragic weakness which prevented writers — and readers — from being at once simple and true.

Writers, Bellow argues, are in a singular positions to cut through the veneer of respectable opinions and remind us the truth of who we are and who we can be:

The intelligent public is wonderfully patient with [writers], continues to read them and endures disappointment after disappointment, waiting to hear from art what it does not hear from theology, philosophy, social theory, and what it cannot hear from pure science. Out of the struggle at the center has come an immense, painful longing for a broader, more flexible, fuller, more coherent, more comprehensive account of what we human beings are, who we are, and what this life is for. At the center humankind struggles with collective powers for its freedom, the individual struggles with dehumanization for the possession of his soul. If writers do not come again into the center it will not be because the center is pre-empted. It is not. They are free to enter. If they so wish.

Echoing the Dante-esque notion of “a love that moves the sun and the other stars,” Bellow closes with a breathtaking contemplation of our deeper search for meaning undergirding all great art and literature — those fragmentary glimpses of luminous lucidity through which we are reminded, although we soon forget again, of our eternal communion with the universe:

The essence of our real condition, the complexity, the confusion, the pain of it is shown to us in glimpses, in [Proust’s] “true impressions.” This essence reveals and then conceals itself. When it goes away it leaves us again in doubt. But we never seem to lose our connection with the depths from which these glimpses come. The sense of our real powers, powers we seem to derive from the universe itself, also comes and goes. We are reluctant to talk about this because there is nothing we can prove, because our language is inadequate and because few people are willing to risk talking about it. They would have to say, “There is a spirit” and that is taboo. So almost everyone keeps quiet about it, although almost everyone is aware of it.

The value of literature lies in these intermittent “true impressions.” A novel moves us back and forth between the world of objects, of actions, of appearances, and that other world from which these “true impressions” come and which moves us to believe that the good we hang onto so tenaciously — in the face of evil, so obstinately — is no illusion.

[…]

Art attempts to find in the universe, in matter as well as in the facts of life, what is fundamental, enduring, essential.

Complement with Dani Shapiro on the “animating presence” of secular spirituality and William Faulkner’s elevating Nobel Prize acceptance speech on the role of the writer as a booster of the human heart, then revisit Bellow on our dance with distraction.

Interview with John Banville, a portrait in ‚The Guardian‘ and more…

Extraordinary interview with the Irish writer John Banville for the German literature TV show ‚Das blaue Sofa‘ from 7th Mar 2014 about his latest novel ‚Ancient Light‘ from 2012 that is published now in Germany.

“All art is an attempt to capture the moment,” he tells me “to stall time in its terrifyingly unstoppable flow. Memory is a kind of back-door way of doing that. But I no longer believe that we remember – I think we invent, and take our inventions for ‘what really happened’. It’s a harmless and consoling bit of self-deception.”

“Oh, of course, one never gets anywhere near what one set out to do. A novel is a wilful beast, and keeps insisting on its own agenda. And language is a terribly slippery, treacherous medium. As I always say: we think we speak, whereas really we are spoken.”

„It all starts with rhythm for me. I love Nabokov’s work, and I love his style. But I always thought there was something odd about it that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Then I read an interview in which he admitted he was tone deaf. And I thought, that’s it—there’s no music in Nabokov, it’s all pictorial, it’s all image-based. It’s not any worse for that, but the prose doesn’t sing. For me, a line has to sing before it does anything else. The great thrill is when a sentence that starts out being completely plain suddenly begins to sing, rising far above itself and above any expectation I might have had for it. That’s what keeps me going on those dark December days when I think about how I could be living instead of writing.“

I love the first sentences of Banville’s ‚The Sea‘: „They departed, the gods, on the day of the strange tide. All morning under a milky sky the waters in the bay had swelled and swelled, rising to unheard-of heights, the small waves creeping over parched sand that for years had known no wetting save for rain and lapping the very bases of the dunes. The rusted hulk of the freighter that had run aground at the far end of the bay longer ago than any of us could remember must have thought it was being granted a relaunch. I would not swim again, after that day. The seabirds mewled and swooped, unnerved, it seemed, by the spectacle of that vast bowl of water bulging like a blister, lead-blue and malignantly agleam. They looked unnaturally white, that day, those birds. The waves were depositing a fringe of soiled yellow foam along the waterline. No sail marred the high horizon. I would not swim, no,not ever again. Someone has just walked over my grave. Someone.“

John Banville: a life in writing

- The Guardian, Friday 29 June 2012 22.55 BST

Just before Christmas last year Caroline Walsh, John Banville’s successor as literary editor of the Irish Times, died unexpectedly. „It was a great shock to all of us,“ he says. „It’s a cliché but she was full of life. It’s hard to believe that she’s gone. I thought I saw her the other day when I was walking around Dublin. I had to remind myself she’s dead. Death is such a strange thing. One minute you’re here and then just gone. You’d think there would be an anteroom, a place where you could be visited before you go.“

Banville dedicated his new novel Ancient Light to Walsh. Although the book was completed before her death, the dedication is fitting. The novel aches with the narrator’s sense of loss for two women: one his dead daughter, the other a lover about whom he reminisces 50 years after their affair in an Irish coastal town. Sixtysomething actor Alex Cleave and his wife still mourn their daughter Catherine, „our Cass“, who apparently killed herself 10 years earlier in Italy.

Cleave recalls that when Cass was little she said she would marry her father and they would have a daughter just like her, so that if she died he would not miss her and be lonely. He resorts to other tricks to mitigate his grief, imagining a multiplicity of universes in one of which Cass did not die, or writing her back to life: „All my dead are alive to me, for whom the past is a luminous and everlasting present; alive to me yet lost, except in the frail afterworld of these words.“

Cleave also recollects his summer-long affair when he was 15 and his lover 35. The book begins: „Billy Gray was my best friend and I fell in love with his mother.“ But is Cleave remembering the affair or making it up as he goes along, victim of what he calls Madam Memory, that „great and subtle dissembler“? In a sense, it doesn’t matter. The important thing is his probably unfulfillable yearning: „I should like to be in love again, I should like to fall in love again, just once more.“

Where did that story come from, I ask the author, hoping for a real-life story of a teenage Banville’s sexual initiation by an Irish version of Anne Bancroft’s Mrs Robinson. After all, Banville, 66, is roughly as old as his narrator. „Oh, I’ve no idea. The problem with doing an interview is that the person who wrote the story ceased to exist every day I got up from the desk. When you’re writing there’s a deep deep level of concentration way below your normal self. This strange voice, these strange sentences come out of you. When I was young I thought I was in control of everything. Now I realise it’s much more a process of dreaming.“

Banville is fond of the characters he’s dreamed up, especially the remembered lover, Mrs Gray. „I like her. She constantly laughs at him. That, not the sex, would have helped him grow up. To be laughed at by a grown-up woman is one of the great experiences of life – I mean laughed at fondly.“ Howard Jacobson once wrote that his ambition was to see women’s throats – to make them laugh so much they hurled back their heads in pleasure. „That’s a lovely notion,“ Banville says. And then, typically, he has a story to trump it. „Once I was having lunch with a woman friend of mine, and there had been some things in the paper about my marriage breaking up – I had a bad reputation.“ (Banville is married to the American weaver Janet Dunham, whom he met while travelling in the US in 1968 and with whom he has two sons; he also has two daughters from his relationship with Patricia Quinn, former director of the Arts Council of Ireland.) „There were two women at the next table, and my friend was laughing so much that from where they were sitting it looked as if she was weeping. When they left they looked at me as if to say: ‚There you go he’s doing it again.‘ What a monster I must be.“

Could the affair in the new novel have been narrated from Mrs Gray’s point of view? „I don’t think so because I’ve never understood women. Never will, don’t want to. I’m in love with all of them, always have been fascinated by them. Not just for sex but because they always do the unexpected – at least I don’t expect what they do. They say: ‚We’re ordinary, we’re just like you.‘ I say: ‚You’re not. You’re magical creatures.‘ I’m a hopeless 19th-century romantic.“

We’re lunching at a Dublin restaurant the day after Ireland’s footballing humiliation by Spain. A nation, Banville excepted, mourns. „I was at a party once and everybody was talking about some soccer game. Apart from Harry Crosbie, an entrepreneur. He leaned across to me and said: ‚Imagine caring who won.‘ I said to him: ‚Friends for life, Harry. Friends for life.'“

So forget football and tell me about the psychic wound that made you a writer. „Seamus Heaney tells this wonderful story,“ Banville replies. „He was talking to a Finnish poet, who was rather dour as Finnish poets tend to be and said he was having terrible troubles with his parents. The poet said: ‚What about you?‘ Seamus said: ‚I rather liked my parents.‘ The poet said: ‚You really have a problem!‘

„Like Seamus, I rather liked my parents. Lower middle class, small town.“ Banville was born in Wexford in 1945. He once said he didn’t bother memorising Wexford’s street names, so sure was he that he’d leave fast and never return. Ironically, he’s returned to plunder that childhood frequently. „Sat in the fields reciting Keats to the skylarks. My brother was eight years older than I was. He was in Africa when I was a teenager. My sister was working in Dublin. So I was an only child most of my teenage years. Adored by my mother, tolerated by my father. If there is a psychic wound there, I’m their psychic wound. I must have been the most hideously irritating teenager. I thought I was smarter than them. I wouldn’t have tolerated me if I’d been them.“

Banville started writing aged 12, after being bowled over by Joyce’s Dubliners. He tapped out Joycean pastiches on Aunt Sadie’s Remington typewriter. One began: „The white May blossom swooned slowly into the open mouth of the grave.“ „The arrogance! I knew nothing of death.“ He also painted. „Couldn’t draw, no sense of draughtsmanship or colour.“ But painting at least made him look intensely. He avoided university. „I thought I knew it all.“ Instead he got a job as a clerk at Aer Lingus. The job gave him freedom to write and opportunity to travel. „I would write at night after a day’s work. I was very disciplined. I’d given up Catholicism in my teens but something of it stays with me. I try to create the perfect sentence – that’s as close to godliness as I can get.“

Later, he worked as copy editor first for the Irish Press and then the Irish Times, writing by day, subbing at night. „Graham Greene was right. He said that if you’re going to be a novelist, working as a subeditor is the perfect job. You write during the day, go to work at night, the best of your energy is during the day. An old editor of mine said subeditors were people who change other people’s words and go home in the dark.“

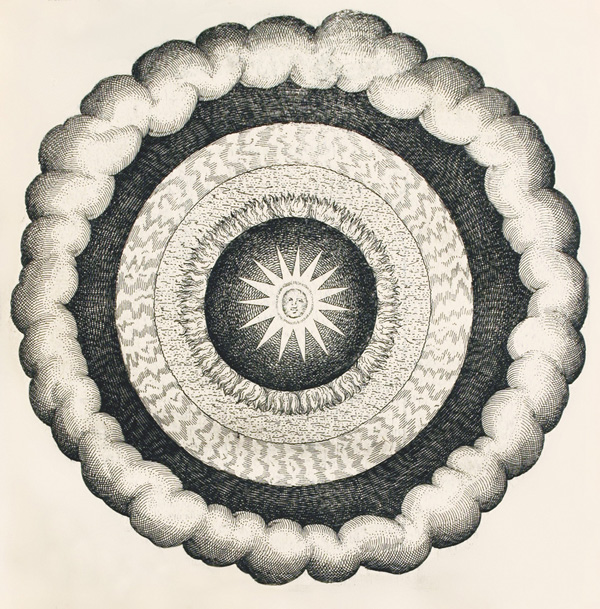

His first book, Long Lankin (1970), was a collection of short stories and a novella. Within three years he had published two novels as well, and reckons that the second, Birchwood, led him up a literary dead end. „It was my Irish novel and I didn’t know what to do next. I thought of giving up. I hated my Irish charm. Irish charm, as we all know, is entirely fake.“ Instead, he reinvented himself as a European novelist of ideas, writing novels involving Renaissance scientists. Doctor Copernicus, Kepler and The Newton Letter were, he argues, books written by a self-confident man from whom he sounds estranged. „Had he been to university, some professor would have warned him off those subjects. But I was free because arrogant, arrogant because free. Some say those are my best books. I think I took a wrong turning with them. Today if I can write a sentence that captures the play of light on a wall, I’m happy.“

He reckons to have had a nervous breakdown while writing Mefisto (1986), the planned fourth part of that scientific tetralogy. „It was then that I stopped trying to be in control and trusted myself to dream in my writing.“ When the book was critically ignored, he retreated wounded to his garden and grew lettuces for a summer.

Banville once said of his books that „I hate them all“. Is that affectation? „They embarrass me because they’re all failures. We’re aiming for perfection and never attain it. It’s become a cliché but, as Beckett wrote, ‚Fail again. Fail better.‘ What one does is so little compared to one’s ambitions for it.“

He hasn’t read reviews for many years, which seems odd for such a prolific reviewer. Why? „I spend two, three to five years writing a book. I know its failings. I know the few areas in which it’s succeeded. The only person who can’t read this book is me because I bring to it all the history, all the dead cats and slime and that Tuesday afternoon when you said ‚Fuck it‘, and you let the paragraph go.“

One reason he ought to read reviews of his books is that most of them are eulogies. Reviewing Banville’s 1997 novel The Untouchable in the Observer, George Steiner wrote: „Banville is the most intelligent and stylish novelist currently at work in English … The mien is austere and Victorian; the awareness, the ironic readings of the contemporary are razor-sharp.“

Has he ever stopped ventriloquising others and written in his own voice? „Only once. In The Book of Evidence“ – his 1989 Booker-shortlisted novel about a man who murders a servant while trying to steal a painting from a neighbour – „where the narrator says: ‚I have never really got used to being on this earth. Sometimes I think our presence here is due to a cosmic blunder, that we were meant for another planet altogether, with other arrangements, and other laws, and other, grimmer skies.‘ I believe this world is too gentle for us. We should have been in an iron world, not this one. I used to drive in to work at five o’clock in the evening looking at the sky, thinking ‚Who arranged this exquisite thing?‘ How I wasn’t killed, I don’t know. This world is terrible and savage but it’s absolutely exquisite and we don’t deserve it.“

In 2005, Banville won the Booker prize for The Sea, about an art historian returning to a seaside village where he spent a childhood holiday. The award was surprising, as Banville seemed to have queered his pitch. In 1981 he wrote to the Guardian waspishly requesting that that year’s Booker prize, for which he was „runner-up to the shortlist of contenders“, be given to him so that he could use the money to buy every copy of the longlisted books in Ireland and donate them to libraries, „thus ensuring that the books not only are bought but also read – surely a unique occurrence.“

Worse yet, he had – by his own admission – made powerful enemies earlier in 2005 with his New York Review of Books demolition of Ian McEwan’s novel Saturday, which he called „a dismayingly bad book“. „It looked like one novelist kicking another novelist, and that wasn’t what it was at all. As far as one can be disinsterested, I was reviewing it in a disinterested way. But, boy, have I made a lot of enemies.“

Among those enemies, he feared, was John Sutherland, Booker chairman in 2005. But, with the judges poised between The Sea and Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, Sutherland cast his deciding vote in favour of Banville. „Curious because he’d been furious with me for my review of McEwan.“ Then he bit the hand. „I blew the whole bloody thing by being michievious in an interview on BBC2 with Kirsty Wark.“ He said: „Whether The Sea is a successful work of art is not for me to say, but a work of art is what I set out to make. The kind of novels that I write very rarely win the Man Booker prize, which in general promotes good, middlebrow fiction.“

So does Ancient Light stand a chance of being shortlisted for the Booker? „I think they may as well call the whole thing off and give me the prize now!“ Banville has written a film adaptation of The Sea, which is to be directed by Stephen Brown and will star Ciarán Hinds. Like his prolific book reviewing, film writing is an enjoyable sideline from fiction. He has an as yet unfilmed screenplay on the life of his Irish revolutionary hero Roger Casement, which he wrote for director Neil Jordan. He wrote a script, based on a George Moore short story, for Glenn Close to play a 19th-century Dublin cross-dresser in last year’s film Albert Nobbs. Now he’s working with director Jonathan Kent on an Irish-set adaptation of Turgenev’s A Month in the Country.

„My ideal would be to be one of those hacks in a bungalow in the Hollywood Hills in the late 40s, and a producer with a cigar in his mouth says: ‚We need two scenes by 6 o’clock and they’d better be good, kid, or you’re off the movie.‘ I’d love to have worked like that.“ It would be an antidote to the solitary torture of being John Banville, maker of baroquely structured Nabokovian works of art. For similar reasons, no doubt, after The Sea, he devised the nom de plume Benjamin Black, whose crime novels today are more prominently displayed than Banville’s books at Dublin airport’s bookshops. Why did he create Black? „I love being a craftsman. I love writing reviews. I quite like being Benjamin Black. But being John Banville I absolutely hate.“ No wonder: it is Banville’s stated ambition to give his prose „the kind of denseness and thickness that poetry has“. „On a good day Banville can’t write more than 400 words, but they are all in more or less the right order. With Black it’s 10 times more.“

Being Black also gives him a break from being misconstrued as Banville, literary sage of the emotions. „I have this friend who has an incredibly complicated love life and she says: ‚Advise me, John.‘ I say: ‚I can’t. Just because I write about something doesn’t mean I know anything about it.‘ One of my models is Kafka, who said: ‚Never again psychology!‘ He’s right – artists are witnesses, we present the surface. As Nietzsche said, surfaces are where the real depth is. „

In Ancient Light the narrator says he doesn’t understand human motivation, his own least of all. „That’s true of all of us, isn’t it? Do you think you understand yourself?“ He maintains we get further from self-understanding as we get older. „I used to think age brings wisdom, but it only brings confusion. A friend of mine visited Beckett in his old folks‘ home in Paris and he said he was getting so old he was forgetting so many things. My friend sympathised and Beckett said: ‚No, no – it’s wonderful!‘ I know what he means: so much trivia gets wiped.

„It’s quite comic, the spectacle of one’s own creeping dissolution. Not so much the usual funny things of forgetting why you went upstairs, but actually to watch the physical stuff decay. It’s definitely comic. I hadn’t seen a profile photograph of myself for about 30 years until the other day. I thought: your hair’s going as well.“

Banville stands to go: „You have enough. You have the jokes, the arrogance and the sermon.“ I wanted more, I tell him. Over his shoulder he gives me a parting joke: „It’s no good – I can’t do humility.“

Paris Review – The Art of Fiction No. 163, William T. Vollmann

Paris Review – The Art of Fiction No. 163, William T. Vollmann.

William T. Vollmann, the author of eleven books, all published since 1987, has become known for his highly unusual prolificity, for his extraordinary stylistic pyrotechnics, for the unique engagement of his own personality with his work, and for the quite staggering ambition of his literary projects. He also has begun to achieve a certain notoriety for his parallel career as a professional adventurer.

At twenty-two, Vollmann traveled to Afghanistan in the hopes of aiding the mujahideen rebels in their struggle against the Soviet army. His less than successful efforts are recounted in the tragicomic memoir An Afghanistan Picture Show (1992). In the early eighties, while living in San Francisco, he befriended the prostitutes in the Tenderloin to gather material for his first story collection, The Rainbow Stories (1989).

For over a decade Vollmann has been at work on Seven Dreams: A Book of North American Landscapes, a grand multinovel project to recreate the history of the North American continent. “I’d like to see these books taught in history classes,” he has said. The Ice-Shirt (1990) recounts the brief colonization of a part of the continent by the Vikings; Fathers and Crows (1992) tells of the relationships among the French Jesuit priests and the Iroquois and Huron Native Americans; and The Rifles (1994), the third novel to be written (actually the sixth in the series), focuses on the exploits of British explorer Sir John Franklin, who died on a naval expedition to the Canadian Arctic. To research The Rifles, Vollmann spent two weeks at an abandoned weather station at the magnetic North Pole, where his sleeping bag didn’t warm him and he began to hallucinate from lack of sleep: “Every night now he wondered if he would live until morning,” he writes.

Vollmann’s other works include the short-story collection Thirteen Stories and Thirteen Epitaphs (1991), as well as the novels Whores for Gloria; or, Everything Was Beautiful Until the Girls Got Anxious (1992) and The Royal Family, which was published earlier this year.

Though it was updated this fall, the main portion of this interview took place in New York City in the fall of 1993. Vollmann was traveling to promote his most recent publication, the episodic novel Butterfly Stories. We talked in the small living room of his sister Sarah’s Hell’s Kitchen apartment, where Vollmann was staying while in New York.

‚The Letter of Lord Chandos‘ by Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Hugo von Hofmannsthal

The Letter of Lord Chandos

THIS is the letter Philip, Lord Chandos, younger son of the Earl of Bath, wrote to Francis Bacon, later Baron Verulam, Viscount St. Albans, apologizing for his complete abandonment of literary activity.

IT IS kind of you, my esteemed friend, to condone my two years of silence and to write to me thus. It is more than kind of you to give to your solicitude about me, to your perplexity at what appears to you as mental stagnation, the expression of lightness and jest which only great men, convinced of the perilousness of life yet not discouraged by it, can master.

You conclude with the aphorism of Hippocrates, „Qui gravi morbo correpti dolores non sentiunt, us mens aegrotat“ (Those who do not perceive that they are wasted by serious illness are sick in mind), and suggest that I am in need of medicine not only to conquer my malady, but even more, to sharpen my senses for the condition of my inner self. I would fain give you an answer such as you deserve, fain reveal myself to you entirely, but I do not know how to set about it. Hardly do I know whether I am still the same person to whom your precious letter is addressed. Was it I who, now six-and-twenty, at nineteen wrote The New Paris, The Dream of Daphne, Epithalamium, those pastorals reeling under the splendour of their words-plays which a divine Queen and several overindulgent lords and gentlemen are gracious enough still to remember? And again, was it I who, at three-and-twenty, beneath the stone arcades of the great Venetian piazza, found in myself that structure of Latin prose whose plan and order delighted me more than did the monuments of Palladio and Sansovino rising out of the sea? And could I, if otherwise I am still the same person, have lost from my inner inscrutable self all traces and scars of this creation of my most intensive thinking-lost them so completely that in your letter now lying before me the title of my short treatise stares at me strange and cold? I could not even comprehend, at first, what the familiar picture meant, but had to study it word by word, as though these Latin terms thus strung together were meeting my eye for the first time. But I am, after all, that person, and there is rhetoric in these questions-rhetoric which is good for women or for the House of Commons, whose power, however, so overrated by our time, is not sufficient to penetrate into the core of things. But it is my inner self that I feel bound to reveal to you-a peculiarity, a vice, a disease of my mind, if you like-if you are to understand that an abyss equally unbridgeable separates me from the literary works lying seemingly ahead of me as from those behind me: the latter having become so strange to me that I hesitate to call them my property.

I know not whether to admire more the urgency of your benevolence or the unbelievable sharpness of your memory, when you recall to me the various little projects I entertained during those days of rare enthusiasm which we shared together. True, I did plan to describe the first years of the reign of our glorious sovereign, the late Henry VIII. The papers bequeathed to me by my grandfather, the Duke of Exeter, concerning his negotiations with France and Portugal, offered me some foundation. And out of Sallust, in those happy, stimulating days, there flowed into me as though through never~ongested conduits the realization of form-that deep, true, inner form which can be sensed only beyond the domain of rhetorical tricks: that form of which one can no longer say that it organizes subject-matter, for it penetrates it, dissolves it, creating at once both dream and reality, an interplay of eternal forces, something as marvellous as music or algebra. This was my most treasured plan.

But what is man that he should make plans!

I also toyed with other schemes. These, too, your kind letter conjures up. Each one, bloated with a drop of my blood, dances before me like a weary gnat against a sombre wall whereon the bright sun of halcyon days no longer lies.

I wanted to decipher the fables, the mythical tales bequeathed to us by the Ancients, in which painters and sculptors found an endless and thoughtless pleasure decipher them as the hieroglyphs of a secret, inexhaustible wisdom whose breath I sometimes seemed to feel as though from behind a veil.

I well remember this plan. It was founded on I know not what sensual and spiritual desire: as the hunted hart craves water, so I craved to enter these naked, glistening bodies, these sirens and dryads, this Narcissus and Proteus, Perseus and Actaeon. I longed to disappear in them and talk out of them with tongues. And I longed for more. I planned to start an Apophthegmata, like that composed by Julius Caesar: you will remember that Cicero mentions it in a letter. In it I thought of setting side by side the most memorable sayings which-while associating with the learned men and witty women of our time, with unusual people from among the simple folk or with erudite and distinguished personages I had managed to collect during my travels. With these I meant to combine the brilliant maxims and reflections from classical and Italian works, and anything else of intellectual adornment that appealed to me in books, in manuscripts or conversations; the arrangement, moreover, of particularly beautiful festivals and pageants, strange crimes and cases of madness, descriptions of the greatest and most characteristic architectural monuments in the Netherlands, in France and Italy; and many other things. The whole work was to have been entitled Nosce te ipsum.

To sum up: In those days I, in a state of continuous intoxication, conceived the whole of existence as one great unit: the spiritual and physical worlds seemed to form no contrast, as little as did courtly and bestial conduct, art and barbarism, solitude and society; in everything I felt the presence of Nature, in the aberrations of insanity as much as in the utmost refinement of the Spanish ceremonial; in the boorishness of young peasants no less than in the most delicate of allegories; and in all expressions of Nature I felt my-self. When in my hunting lodge I drank the warm foaming milk which an unkempt wench had drained into a wooden pail from the udder of a beautiful gentle~yed cow, the sensation was no different from that which I experienced when, seated on a bench built into the window of my study, my mind absorbed the sweet and foaming nourishment from a book. The one was like the other: neither was superior to the other, whether in dreamlike celestial quality or in physical intensity-and thus it prevailed through the whole expanse of life in all directions; everywhere I was in the centre of it, never suspecting mere appearance: at other times I divined that all was allegory and that each creature was a key to all the others; and I felt myself the one capable of seizing each by the handle and unlocking as many of the others as were ready to yield. This explains the title which I had intended to give to this encyclopedic book.

To a person susceptible to such ideas, it might appear a well-designed plan of divine Providence that my mind should fall from such a state of inflated arrogance into this extreme of despondency and feebleness which is now the permanent condition of my inner self. Such religious ideas, however, have no power over me: they belong to the cobwebs through which my thoughts dart out into the void, while the thoughts of so many others are caught there and come to rest. To me the mysteries of faith have been condensed into a lofty allegory which arches itself over the fields of my life like a radiant rainbow, ever remote, ever prepared to recede should it occur to me to rush toward it and wrap myself into the folds of its mantle.

But, my dear friend, worldly ideas also evade me in a like manner. How shall I try to describe to you these strange spiritual torments, this rebounding of the fruit-branches above my outstretched hands, this recession of the murmuring stream from my thirsting lips?

My case, in short, is this: I have lost completely the ability to think or to speak of anything coherently.

At first I grew by degrees incapable of discussing a loftier or more general subject in terms of which everyone, fluently and without hesitation, is wont to avail himself. I experienced an inexplicable distaste for so much as uttering the words spirit, soul, or body. I found it impossible to express an opinion on the affairs at Court, the events in Parliament, or whatever you wish. This was not motivated by any form of personal deference (for you know that my candour borders on imprudence), but because the abstract terms of which the tongue must avail itself as a matter of course in order to voice a judgment-these terms crumbled in my mouth like mouldy fungi. Thus, one day, while reprimanding my four-year-old daughter, Katherina Pompilia, for a childish lie of which she had been guilty and demonstrating to her the necessity of always being truthful, the ideas streaming into my mind suddenly took on such iridescent colouring, so flowed over into one another, that I reeled off the sentence as best I could, as if suddenly overcome by illness. Actually, I did feel myself growing pale, and with a violent pressure on my forehead I left the child to herself, slammed the door behind me, and began to recover to some extent only after a brief gallop over the lonely pasture.

Gradually, however, these attacks of anguish spread like a corroding rust. Even in familiar and humdrum conversation all the opinions which are generally expressed with ease and sleep-walking assurance became so doubtful that I had to cease altogether taking part in such talk. It filled me with an inexplicable anger, which I could conceal only with effort, to hear such things as: This affair has turned out well or ill for this or that person; Sheriff N. is a bad, Parson T. a good man; Farmer M. is to be pitied, his sons are wasters; another is to be envied because his daughters are thrifty; one family is rising in the world, another is on the downward path. All this seemed as indemonstrable, as mendacious and hollow as could be. My mind compelled me to view all things occurring in such conversations from an uncanny closeness. As once, through a magnifying glass, I had seen a piece of skin on my little finger look like a field full of holes and furrows, so I now perceived human beings and their actions. I no longer succeeded in comprehending them with the simplifying eye of habit. For me everything disintegrated into parts, those parts again into parts; no longer would anything let itself be encompassed by one idea. Single words floated round me; they congealed into eyes which stared at me and into which I was forced to stare back-whirlpools which gave me vertigo and, reeling incessantly, led into the void.

I tried to rescue myself from this plight by seeking refuge in the spiritual world of the Ancients. Plato I avoided, for I dreaded the perilousness of his imagination. Of them all, I intended to concentrate on Seneca and Cicero. Through the harmony of their clearly defined and orderly ideas I hoped to regain my health. But I was unable to find my way to them. These ideas, I understood them well: I saw their wonderful interplay rise before me like magnificent fountains upon which played golden balls. I could hover around them and watch how they played, one with the other; but they were concerned only with each other, and the most prof6und, most personal quality of my thinking remained excluded from this magic circle. In their company I was overcome by a terrible sense of loneliness; I felt like someone locked in a garden surrounded by eyeless statues. So once more I escaped into the open.

Since that time I have been leading an existence which I fear you can hardly imagine, so lacking in spirit and thought is its flow: an existence which, it is true, differs little from that of my neighbours, my relations, and most of the landowning nobility of this kingdom, and which is not utterly bereft of gay and stimulating moments. It is not easy for me to indicate wherein these good moments subsist; once again words desert me. For it is, indeed, something entirely unnamed, even barely nameable which, at such moments, reveals itself to me, filling like a vessel any casual object of my daily surroundings with an overflowing flood of higher life. I cannot expect you to understand me without examples, and I must plead your indulgence for their absurdity. A pitcher, a harrow abandoned in a field, a dog in the sun, a neglected cemetery, a cripple, a peasant’s hut-all these can become the vessel of my revelation. Each of these objects and a thousand others similar, over which the eye usually glides with a natural indifference, can suddenly, at any moment (which I am utterly powerless to evoke), assume for me a character so exalted and moving that words seem too poor to describe it. Even the distinct image of an absent object, in fact, can acquire the mysterious function of being filled to the brim with this silent but suddenly rising flood of divine sensation. Recently, for instance, I had given the order for a copious supply of rat-poison to be scattered in the milk cellars of one of my dairy-farms. Towards evening I had gone off for a ride and, as you can imagine, thought no more about it. As I was trotting along over the freshly-ploughed land, nothing more alarming in sight than a scared covey of quail and, in the distance, the great sun sinking over the undulating fields, there suddenly loomed up before me the vision of that cellar, resounding with the death-struggle of a mob of rats. I felt everything within me: the cool, musty air of the cellar filled with the sweet and pungent reek of poison, and the yelling of the death cries breaking against the mouldering walls; the vain convulsions of those convoluted bodies as they tear about in confusion and despair; their frenzied search for escape, and the grimace of icy rage when a couple collide with one another at a blocked-up crevice. But why seek again for words which I have foresworn! You remember, my friend, the wonderful description in Livy of the hours preceding the destruction of Alba Longa: when the crowds stray aimlessly through the streets which they are to see no more . . . when they bid farewell to the stones beneath their feet. I assure you, my friend, I carried this vision within me, and the vision of burning Carthage, too; but there was more, something more divine, more bestial; and it was the Present, the fullest, most exalted Present. There was a mother, surrounded by her young in their agony of death; but her gaze was cast neither toward the dying nor upon the merciless walls of stone, but into the void, or through the void into Infinity, accompanying this gaze with a gnashing of teeth!-A slave struck with helpless terror standing near the petrifying Niobe must have experienced what I experienced when, within me, the soul of this animal bared its teeth to its monstrous fate.

Forgive this description, but do not think that it was pity I felt. For if you did, my example would have been poorly chosen. It was far more and far less than pity: an immense sympathy, a flowing over into these creatures, or a feeling that an aura of life and death, of dream and wakefulness, had flowed for a moment into them-but whence? For what had it to do with pity, or with any comprehensible concatenation of human thought when, on another evening, on finding beneath a nut-tree a half-filled pitcher which a gardener boy had left there, and the pitcher and the water in it, darkened by the shadow of the tree, and a beetle swimming on the surface from shore to shor~when this combination of trifles sent through me such a shudder at the presence of the Infinite, a shudder running from the roots of my hair to the marrow of mv heels? What was it that made me want to break into words which, I know, were I to find them, would force to their knees those cherubim in whom I do not believe? What made me turn silently away from this place? Even now, after weeks, catching sight of that nut-tree, I pass it by with a shy sidelong glance, for I am loath to dispel the memory of the miracle hovering there round the trunk, loath to scare away the celestial shudders that still linger about the shrubbery in this neighbourhood! In these moments an insignificant creature-a dog, a rat, a beetle, a crippled apple tree, a lane winding over the hill, a moss-covered stone, mean more to me than the most beautiful, abandoned mistress of the happiest night. These mute and, on occasion, inanimate creatures rise toward me with such an abundance, such a presence of love, that my enchanted eye can find nothing in sight void of life. Everything that exists, everything I can remember, everything touched upon by my confused thoughts, has a meaning. Even my own heaviness, the general torpor of my brain, seems to acquire a meaning; I experience in and around me a blissful, never-ending interplay, and among the objects playing against one another there is not one into which I cannot flow. To me, then, it is as though my body consists of nought but ciphers which give me the key to everything; or as if we could enter into a new and hopeful relationship with the whole of existence if only we begin to think with the heart. As soon, however, as this strange enchantment falls from me, I find myself confused; wherein this harmony transcending me and the entire world consisted, and how it made itself known to me, I could present in sensible words as little as I could say anything precise about the inner movements of my intestines or a congestion of my blood.

Apart from these strange occurrences, which, incidentally, I hardly know whether to ascribe to the mind or the body, I live a life of barely believable vacuity, and have difficulties in concealing from my wife this inner stagnation, and from my servants the indifference wherewith I contemplate the affairs of my estates. The good and strict education which I owe to my late father and the early habit of leaving no hour of the day unused are the only things, it seems to me, which help me maintain towards the outer world the stability and the dignified appearance appropriate to my class and my person.

I am rebuilding a wing of my house and am capable of conversing occasionally with the architect concerning the progress of his work; I administer my estates, and my tenants and employees may find me, perhaps, somewhat more taciturn but no less benevolent than of yore. None of them, standing with doffed cap before the door of his house while I ride by of an evening, will have any idea that my glance, which he is wont respectfully to catch, glides with longing over the rickety boards under which he searches for earthworms for fishing-bait; that it plunges through the latticed window into the stuffy chamber where, in a corner, the low bed with its chequered linen seems forever to be waiting for someone to die or another to be born; that my eye lingers long upon the ugly puppies or upon a cat stealing stealthily among the flower-pots; and that it seeks among all the poor and clumsy objects of a peasant’s life for the one whose insignificant form, whose unnoticed being, whose mute existence, can become the source of that mysterious, wordless, and boundless ecstasy. For my unnamed blissful feeling is sooner brought about by a distant lonely shepherd’s fire than by the vision of a starry sky, sooner by the chirping of the last dying cricket when the autumn wind chases wintry clouds across the deserted fields than by the majestic booming of an organ. And in my mind I compare myself from time to time with the orator Crassus, of whom it is reported that he grew so excessively enamoured of a tame lamprey-a dumb, apathetic, red-eyed fish in his ornamental pond-that it became the talk of the town; and when one day in the Senate Domitius reproached him for having shed tears over the death of this fish, attempting thereby to make him appear a fool, Crassus answered, „Thus have I done over the death of my fish as you have over the death of neither your first nor your second wife.“

I know not how oft this Crassus with his lamprey enters mv mind as a mirrored image of my Self, reflected across the abyss of centuries. But not on account of the answer he gave Domitius. The answer brought the laughs on his side, and the whole affair turned into a jest. I, however, am deeply affected by the affair, which would have remained the same even had Domitius shed bitter tears of sorrow over his wives. For there would still have been Crassus, shedding tears over his lamprey. And about this figure, utterly ridiculous and contemptible in the midst of a world-governing senate discussing the most serious subjects, I feel compelled by a mysterious power to reflect in a manner which, the moment I attempt to express it in words, strikes me as supremely foolish.

Now and then at night the image of this Crassus is in my brain, like a splinter round which everything festers, throbs, and boils. It is then that I feel as though I myself were about to ferment, to effervesce, to foam and to sparkle. And the whole thing is a kind of feverish thinking, but thinking in a medium more immediate, more liquid, more glowing than words. It, too, forms whirlpools, but of a sort that do not seem to lead, as the whirlpools of language, into the abyss, but into myself and into the deepest womb of peace.

I have troubled you excessively, my dear friend, with this extended description of an inexplicable condition which is wont, as a rule, to remain locked up in me.

You were kind enough to express your dissatisfaction that no book written by me reaches you any more, „to compensate for the loss of our relationship.“ Reading that, I felt, with a certainty not entirely bereft of a feeling of sorrow, that neither in the coming year nor in the following nor in all the years of this my life shall I write a book, whether in English or in Latin: and this for an odd and embarrassing reason which I must leave to the boundless superiority of your mind to place in the realm of physical and spiritual values spread out harmoniously before your unprejudiced eye: to wit, because the language in which I might be able not only to write but to think is neither Latin nor English, neither Italian nor Spanish, but a language none of whose words is known to me, a language in which inanimate things speak to me and wherein I may one day have to justify myself before an unknown judge.

Fain had I the power to compress in this, presumably my last, letter to Francis Bacon all the love and gratitude, all the unmeasured admiration, which I harbour in my heart for the greatest benefactor of my mind, for the foremost Englishman of my day, and which I shall harbour therein until death break it asunder.

This 22 August, A.D. 1603

PHI. CHANDOS