“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way… As a man is, so he sees.”

Quelle: William Blake’s Most Beautiful Letter: A Timeless Defense of the Imagination and the Creative Spirit

“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way… As a man is, so he sees.”

Quelle: William Blake’s Most Beautiful Letter: A Timeless Defense of the Imagination and the Creative Spirit

It’s 1965. Truman Capote was a known figure on the literary scene and a member of the global social jet set. His bestselling books Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s had made him …

Quelle: How Truman Capote Was Destroyed by His Own Masterpiece

The author of “Figuring” (and the brain behind the Brain Pickings website) likes how children’s books speak “a language of absolute sincerity, so deliciously countercultural in our age of cynicism.”

What books are on your nightstand?

I don’t have a nightstand per se — my bedroom is rather ascetic, with only a bed nestled between the constellation-painted walls. I do tend to keep a rotating selection of longtime favorites near or in it, to dip into before sleep — “The Little Prince” (which I reread at least once a year every year, and somehow find new wisdom and pertinence to whatever I am going through at the moment), “The Lives of the Heart,” by Jane Hirshfield, “Hope in the Dark,” by Rebecca Solnit, Thoreau’s diaries, “How the Universe Got Its Spots,” by Janna Levin. Of the piles that inevitably accumulate in every room of my house, friends’ books I have recently read and loved tower nearest the bed — part synonym and part antonym to the lovely Japanese concept of tsundoku, the guilt-pile of books acquired with the intention of reading but left unread. Currently among my anti-tsundoku: “Time Travel,” by James Gleick, “Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine,” by Alan Lightman, “Little Panic,” by Amanda Stern, “Inheritance,” by Dani Shapiro, and an exhibition catalog — which, in her case, is part poetry and part philosophy — by Ann Hamilton.

What’s the last great book you read?

I read multiple books each week and have no qualms about abandoning what fails to captivate me, so I tend to love just about everything I finish. At this particular moment, I am completely smitten with Jill Lepore’s history of America — what a rare masterwork of rigorous scholarship with a poetic sensibility — but I am barely a quarter through, so I’d be cheating if I counted it as read.

I only recently discovered, and absolutely loved, “The Living Mountain,” by the Scottish mountaineer and poet Nan Shepherd — part memoir, part field notebook, part lyrical meditation on nature and our relationship with it, evocative of Rachel Carson and Henry Beston and John Muir. Shepherd composed it sometime around World War II, but kept it in a drawer for nearly four decades, until the final years of her life. Decades after her death, her work — much of it by then out of print — was rediscovered and championed by Robert Macfarlane, a splendid nature writer himself.

Are there any classic novels that you only recently read for the first time?

Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.” I am filled with disbelief bordering on shame that I went this long without it. A book that gives the English language back to itself and your conscience back to itself.

Do your blog posts grow out of whatever you happen to be reading at the time? Or do you pick books specifically with Brain Pickings in mind?

I don’t see my website as a separate entity or any sort of media outlet — it is the record and reflection of my inner life, my discourse with ideas and questions through literature, my extended marginalia. It is a “blog” in the proper sense — a “web log,” part commonplace book and part ledger of a life. Nothing on it is composed for an audience. I write about what I read, and I read to process what I dwell in, mentally and emotionally. The wondrous thing about being human — the beauty and banality of it — is that we all tend to dwell in the same handful of elemental struggles, joys and sorrows, which is why a book one person writes may help another process her own life a century later, and why a “blog” by a solitary stranger may speak to many other solitary dwellers across time and space.

What moves you most in a work of literature?

Rhythm, texture, splendor of sentiment in language, unsentimental soulfulness.

Which genres do you especially enjoy reading? And which do you avoid?

I read mostly nonfiction and poetry. But I also don’t believe in genre as a defining feature of substance. Ursula K. Le Guin’s fantasy is animated by rich moral philosophy. Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel “Are You My Mother?” is replete with more insight into the human psyche than most books in the psychology section of the bookstore. Great children’s books speak to the most elemental truths of existence, and speak in the language of children — a language of absolute sincerity, so deliciously countercultural in our age of cynicism.

How do you organize your books?

My children’s book library is organized by color, everything else by subject and substance first — science, poetry, biographies and autobiographies, diaries and letters, etc. — then within each section, by color. I break the color system for multiple books by the same author on related subjects — amid several Oliver Sacks volumes huddled together, “Hallucinations” beams from the solemn science shelf with its cheerful seizure of cyan.

What’s the best book you’ve ever received as a gift?

My good friend and collaborator Claudia Bedrick, founder of the visionary Enchanted Lion Books, gave me a trilingual pop-up book titled “Little Tree,” by the Japanese graphic designer and book artist Katsumi Komagata — a subtle, stunning meditation on mortality through the life-cycle of a single tree, inspired by a young child struggling to make sense of a beloved father’s death — one of the artist’s close friends. I have a deep love of trees — they have been among my wisest teachers — and recently returned to this book while spending time with one of my own dear friends in the final weeks of her life.

Who is your favorite fictional hero or heroine? Your favorite antihero or villain?

Orlando. It is hard not to fall in love with a beautiful, brilliant creature who changes genders while galloping across three centuries on a pair of “the shapeliest legs” in the land. It is hard not to fall in love with Virginia Woolf’s love for Vita Sackville-West, on whom Orlando is modeled and to whom the book is dedicated. Vita’s son later described the novel as “the longest and most charming love letter in literature.”

In a sense, Orlando is also an antihero in the drama of Woolf’s oppressive heteronormative society — a subversion, a counterpoint to convention, a sentinel of the resistance. A month after the book’s publication, the novelist Radclyffe Hall was tried for obscenity — the same half-coded charge of homosexuality for which Oscar Wilde had been imprisoned a generation earlier — and all printed copies of her lesbian novel “The Well of Loneliness” were destroyed by court order. In response to the trial, Woolf and E. M. Forster wrote in a joint letter of protest: “Writers produce literature, and they cannot produce great literature until they have free minds. The free mind has access to all knowledge and speculation of its age, and nothing cramps it like a taboo.”

What kind of reader were you as a child? Which childhood books and authors stick with you most?

I don’t recall being much of a natural reader early on, but my paternal grandmother made me one. She read me old European fairy tales — Hans Christian Andersen, the uncandied Brothers Grimm. (In the communist Bulgaria of my childhood, the classics of American children’s literature were barred by the Iron Curtain.) I especially loved “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” long before I could fully appreciate the allegorical genius of a brilliant logician. I was awed by my grandmother’s enormous library and was particularly enchanted by the encyclopedias, the way you could pull one out and open to a random page and learn about something thrilling you didn’t even know existed. It is an experience we rarely have anymore in a culture where pointed search has eclipsed serendipitous discovery, leading us to find more and more of what we are already interested in. In a sense, this encyclopedic enchantment and the delight of unbidden discovery have stayed with me and become the backbone of Brain Pickings.

What’s the most interesting thing you learned from a book recently?

From the fantastic new biography of Benjamin Rush by Stephen Fried — my first and foremost writing mentor, whose research intern I was what seems like a lifetime ago, and was even paid two subway tokens per week for the pleasure — I learned that we owe to this “footnoted founder” our formative understanding of mental illness and the then-radical notion that mentally ill people are still people. A century before Nellie Bly’s paradigm-shifting exposé “Ten Days in a Madhouse,” at a time when mental asylum patients were chained to the floor until they “improved,” Rush insisted that their humanity and dignity must be honored in treatment, and pioneered forms of psychiatric care closely resembling the modern. This radical, largehearted reformer was decades, perhaps centuries ahead of his time along so many axes of progress: He became the nation’s pre-eminent champion of public health and public schooling, founded the country’s first rural college, railed against racism, helped African-American clergymen establish two of the nation’s first churches for black congregations, and pushed to extend education to women, African-Americans and non-English-speaking immigrants. (He also penned the most devastating and delightful rant against materialism, condemning America as “a bebanked, and a bewhiskied & a bedollared nation.” I wonder how he would have framed the unfathomable notion that his nation would one day be governed by a billionaire who deals in golf courses, stars in his own reality TV show and bankrolls the business of hate.)

If you could require the president to read one book, what would it be?

I am resisting the cheap impulse to simply say, “Any.” Instead, I’d say Hannah Arendt’s “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” but there is the obvious risk that he might take it for an instructional manual.

Perhaps the safest thing for everyone would be to give the man some poetry — it has a singular way of slipping through the backdoor of the psyche to anneal truth and open even the most fisted heart, “to awaken sleepers by other means than shock,” as the poet Denise Levertov put it. I’d say “Crave Radiance,” by Elizabeth Alexander — one of our finest living poets — but I doubt the fact that she was Barack Obama’s inauguration poet would go over well with the current administration.

Any book by Jane Hirshfield — a splendid poet and an ordained Buddhist — would probably do more good in this country, in the White House and in every home, than all the political op-eds and polemics combined.

You’re organizing a literary dinner party. Which three writers, dead or alive, do you invite?

Rachel Carson, Susan Sontag, Margaret Fuller. It could go one of two ways: intoxicating intellectual repartee — the fiercely opinionated Sontag and Fuller would either love or loathe one another, and Carson would sit in unassuming quietude, speaking only rarely and with the perfect, perfectly formulated sentiment — or literary speed dating for queer women. I, for one, am half-infatuated with all three.

How do you decide what to read next? Is it reviews, word-of-mouth, books by friends, books for research? Does it depend on mood or do you plot in advance?

I often say that literature is the original internet — every allusion, footnote and reference is a hyperlink to another text. Nearly all books I read enter my life through the gateway of other books, which explains why, over the nearly 13-year span of Brain Pickings, my writing has plunged deeper and deeper into the past — this analog web only extends backward in time, for a book can only reference texts previously published. It’s a great antidote to the presentism bias that envelops us, in which we mistake the latest and the loudest — the flotsam of opinion atop social media streams — for the most important, most insightful, most relevant. Right around Ferguson, I discovered through a passing mention in an out-of-print collection of Margaret Mead’s Redbook advice columns her 1970 conversation with James Baldwin, in which they discuss race, gender, identity, democracy, morality, the immigrant experience and a great many other topics of acute relevance today, with tenfold the dignity and depth of insight than our current modes of cultural discourse afford.

What do you plan to read next?

I recently discovered Jenny Uglow’s 2002 biography of the Lunar Men — a small group of freethinking intellectuals, whose members are responsible for the development of the steam engine and a cascade of other advances in science. Somehow, I had completely missed it in my research, even though members of the Lunar Men flit in and out of “Figuring.” The more you read, the more you miss.

Paris. Minuit. 2015. 122 pages.

Source: Football by Jean-Philippe Toussaint | World Literature Today

Who’s the Greatest Unreliable Narrator in Literature?.

Colin Winnette and Jeremy M. Davies each have a new novel featuring an unreliable narrator: Winnette’s Coyote follows a possibly unhinged mother and Davies’s Fancy is about a man looking for a catsitter. Here, once and for all, they (maybe) settle the debate: Who’s the greatest unreliable narrator in literature?

Jeremy M. Davies: Let’s set some ground rules: No Faulkner, no Joyce. No John Dowell, from The Good Soldier. No Nabokov at all. Nabokov dined out on his unreliable narrators for, what, forty years? Who needs those recommendations?

We’ll qualify our assignment by rebranding it „Best Unrecognized Unreliable Narrators.“

Colin Winnette: How unreliable is a narrator really if he or she is famous for being unreliable?

Should Beckett be similarly nixed? I’d otherwise propose Krapp. If unreliable narrators manipulate facts to suit their needs, Krapp—whose existence consists solely of listening to self-selected segments of autobiographical tapes and eating bananas—is the apotheosis of unreliability.

JMD: But I don’t see Krapp as conspicuously dishonest. Deluding himself, I guess, in that he’d like to believe he’s still got something to look forward to, but that’s too universal an unreliability to count for much. Beckett’s major narrators strike me as quite reliable, since they’re not even willing to pretend to be people . . .

CW: Fair. But there’s a case for narrators who are unintentionally misleading or otherwise limited in their ability to tell their story. Alice Soissons, of Gaetan Soucy’s The Little Girl Who Was Too Fond of Matches, is very forthright in her presentation of herself. But, following the death of her father, she’s forced to leave the family farm, and once we’ve seen her through the eyes of others we realize we’ve been misled—not intentionally, but because she’s internalized a life of captivity and abuse.

JMD: Along similar lines, how about the narrator in Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina? It’s not that she isn’t articulate or doesn’t understand her situation. Her perception of it, however, is so skewed and fantastical that we can’t even be certain if the eponymous character, her roommate and confidant, exists.

CW: Perfect. Not necessarily a liar, but existing in a world (or with a mind) that’s more complicated or multiple than a straightforward “account” can grasp.

JMD: Typically, an unreliable narrator is meant to be giving a garbled report of the world—but what happens when the world itself is garbled? (And who would argue that it isn’t?)

CW: How about the protagonist of Horacio Castellanos Moya’s Senselessness? His job—editing an enormous report detailing the gruesome massacres of the indigenous peoples of a Central American country by its military—feeds a growing sense of his being personally imperiled. Is this Moya implicating educated classes who’ve benefitted from past atrocities, or is the narrator simply unable to absorb this violence without making it a part of his own story? Or are his fears valid? The perpetrators of those atrocities are still in power. Garbled and garbling.

JMD: I’m nominating the Physicians’ Desk Reference.

CW: An unreliable narrator is a device the author uses to divide the world of the book. An account that intentionally generates a sense of something else—be it what „actually happened,“ the garbled and garbling world, or just a fog of inconsistencies and fragmentation.

JMD: Right. In the writing-workshop world, the term “unreliable” is too often applied to any old narrator with a theatrical style. There’s Gogol’s madman in „Diary of a …“, for instance, but when the diarist does depart from reality, it’s so clearly signposted as psychosis that we’re dealing less with unreliability than with, well, an efficient execution of the author’s aims.

CW: Two popular contemporary „unreliable narrators“ are Amy Dunne from Gone Girl and the kid from Emma Donoghue’s Room. I’d argue they’re liars, but not unreliable, really; they give us everything we need to understand what happened, and the stories they set out to tell are ultimately resolved. They’re very tidy.

JMD: That’s an excellent distinction. Let’s zero in on voices that call into question even the possibility of reliability.

CW: Along the lines of Malina, there’s the narrator of Lydia Millet’s My Happy Life. Abandoned in a deserted hospital, she’s recording the details of her long and difficult life with what feels like unbelievable optimism and tenderness. Hers could be a defensive position, or it could be psychosis brought on by the tremendous suffering she’s endured. Millet doesn’t wink or give us any perspective outside the narrator’s voice to measure her against. Forced to choose, I’d pick Millet’s narrator over Soucy’s. Grappling with the question of Millet’s narrator’s reliability—and her possible motivations—requires an unnerving kind of empathetic speculation on the reader’s part.

JMD: In Christopher Priest’s The Affirmation, not only do we find—many times over—that events aren’t quite as stated, there’s also the larger question of which (if either) of the two worlds described in parallel is meant to be taken as real. The narrators are honest with neither themselves nor the reader. It’s an excellent book someone needs to put back into print immediately.

CW: Always fighting the good fight!

JMD: And then there’s the great Rudolph Wurlitzer. His first two novels Nog and Flats might outdo Beckett in terms of giving us worlds where everything is disputable, puzzling, unnerving. Or Henry „The Sussex Slasher“ James. The Sacred Fount is his least read major novel, and certainly his oddest. The narrator spends the entire book concocting elaborate deductions about fellow partygoers based on next to no evidence. Even when he’s finally “set straight,” it’s difficult to believe we’ve done anything more than penetrate a single layer of solipsism.

CW: Speaking of solipsism, Marie NDiaye’s narrators have often descended so far into their own universes that they are openly aware of, and oppressed by, the disconnect between reality and their perceptions. Her recent collection, All My Friends, presents multiple examples. First person or close third, the warped lens of the protagonist’s mind is the only view we have. And because the inherent isolation of one’s inner life is so stunting to these characters, the affect is claustrophobic at times, disorienting. Do people see me as I see myself? Are my perceptions accurate? We’re left to wonder, is it even possible to reconcile one’s inner life with those of others without just agreeing to accept the median and ignore the noise around it?

JMD: I think we’re getting there.

CW: If we’re aiming for five, you’ll have to choose between Wurlitzer, Priest, and James.

JMD: Holy Moses. That’s not fair. Aren’t we allowed to have three-way draws?

CW: Not if I have to cut poor Alice Soissons.

JMD: Under protest, I’ll go with James. We can’t go pretending there weren’t unreliable narrators before 1940.

CW: Excellent.

JMD: But I feel unsatisfied.

CW: These lists are meant to be dissatisfying. Half recommendation, half fuel for debate over what we’ve excluded.

JMD: We’re ignoring other forms of the species. Daniel Schreber’s Memoirs of my Nervous Illness isn’t a novel, but an account of the author’s conviction that an egocentric God made wholly of “nerves” wants to turn him into a woman the better to have intercourse with and even impregnate him …

CW: Memoirs are all, de facto, the products of unreliable narrators—though Schreber is, admittedly, an advanced case.

JMD: Our pièce de résistance should be a book without an identifiable first-person narrator that is nonetheless untrustworthy despite pretentions to stability. I’d suggest that the bible of unreliability might be Brian Aldiss’s Report on Probability A, which posits an infinite series of voyeurs in different realities peering into a putatively unbiased, maddeningly precise, and so highly suspicious “report,” itself not unlike a novel . . .

CW: Which leaves us where?

JMD: With quantum physics?

CW: Or . . . the proposition that, while many “unreliable” narrators lie or otherwise obscure information, the terrain of storytelling is such that its more flawed and compelling characters are often those who believe themselves capable of putting together a comprehensive account in the first place—or that such an account is even possible.

5 of the Best Unrecognized Unreliable Narrators and 2 that Will Destroy Your Faith in Reliability Period:

The multiple narrators of Marie Ndiaye’s All My Friends (2004, English trans. 2013)

Unnamed, Horacio Castellanos Moya’s Senselessness (2004, English trans. 2008)

Unnamed, Lydia Millet’s My Happy Life (2007)

Unnamed, Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina (1971, English trans. 1990)

Unnamed, Henry James’s The Sacred Fount (1901)

and

Daniel Schreber, Daniel Schreber’s Memoirs of my Nervous Illness (1903, English trans. 1955)

Reality itself, Brian Aldiss’s Report on Probability A, 1968

Stoner: the must-read novel of 2013 | Books | The Guardian.

On 13 June 1963, the American novelist John Williams wrote from the University of Denver, where he was a professor of English, to his agent Marie Rodell. She had just read his third novel, Stoner, and while clearly admiring it, was also warning him not to get his hopes up. Williams replied: „I suspect that I agree with you about the commercial possibilities; but I also suspect that the novel may surprise us in this respect. Oh, I have no illusions that it will be a ‚bestseller‘ or anything like that; but if it is handled right (there’s always that out) – that is, if it is not treated as just another ‚academic novel‘ by the publisher, as Butcher’s Crossing [his second novel] was treated as a „western“, it might have a respectable sale. The only thing I’m sure of is that it’s a good novel; in time it may even be thought of as a substantially good one.“

How familiar the thought, and the tone, of this will be to almost every practising novelist. The expression of confidence in your own work, without which you would never have started; the wariness in the face of the bitch goddess Success; the caution in raising expectation, but the further caution in not raising it too high; and, finally, the writer’s everlasting „out“ – that if it all goes wrong, it’s probably someone else’s fault.

Stoner was published in 1965, and – as is usually the case – it steered a mid‑course between the novelist’s fears and his hopes. It was respectably reviewed; it had a reasonable sale; it did not become a bestseller; it went out of print. In 1972, Augustus, Williams’s „Roman“ novel, won half the National Book Award for fiction (the other half going to John Barth’s Chimera). It was his largest moment of public success, yet he did not even attend the ceremony; perhaps he was rightly suspicious, as the laudatum pronounced in his absence was strangely disparaging. When he died, two decades later, without publishing any more fiction, the New York Times obituarist treated him as much as a poet and „educator“ as a novelist. But still to come was that factor – identified by Williams in his letter – that novelists often write about, that they fear, but also place their trust in: time. And time has vindicated him way beyond his own modest hope. Fifty years after Williams wrote to his agent, Stoner became a bestseller. A quite unexpected bestseller. A bestseller across Europe. A bestseller publishers themselves could not quite understand. A bestseller of the purest kind – one caused almost entirely by word-of-mouth among readers.

I remember unwrapping my copy of the novel back in March. Like many writers, I get sent far more books than I can possibly read, and the process of triage can be brutal. So: a new paperback (from my own publishers) with a large front-cover strap reading „VINTAGE WILLIAMS“. No Christian name. Raymond Williams? William Carlos Williams? Rowan Williams? Check the spine: John Williams. The classical guitarist? The composer of film music? Neither. Rather, a novel published in the 60s by a dead American I’d never heard of. And then the title: Stoner. Hmmm: were we in for some tranced and tedious discussion of the merits of Moroccan versus Colombian gold? But there was an introduction (and therefore a recommendation) by John McGahern, so it got the first-page test. And Stoner turned out to be the name of the main character, which was a relief. And the prose was clean and quiet; and the tone a little wry. And the first page led to the second, and then what happened was that joyful internal word-of-mouth that sends a reader hurrying from one page to the next; which in turn leads to external word-of-mouth, the pressing of the book on friends, the ordering and sending of copies.

William Stoner, we learn in the book’s first paragraph, was a lifelong academic, who entered the University of Missouri as a student in 1910, and went on to teach there until his death in 1956. The value and purpose of academe is a key concern of the novel, while one of its main sequences describes a long and savage piece of departmental infighting. So Williams was perhaps a little naive, or at least over-hopeful, in thinking his novel wouldn’t, or shouldn’t, be labelled „academic“. In the same way, Butcher’s Crossing (to be reissued by Vintage in January) is indeed a „western“, being set in a Kansas frontier town in the 1870s, with its main action a buffalo hunt in a lost mountain valley as winter approaches. It is so historically and anatomically precise, I am confident that, if you gave me a sharp knife, a horse and a rope, I could now skin a buffalo (though someone else would have to kill it first). Butcher’s Crossing is a very good „western“, as Stoner is a very good „academic novel“ – and, in each case, being „very good“ means that the novels slip their identifying tag.

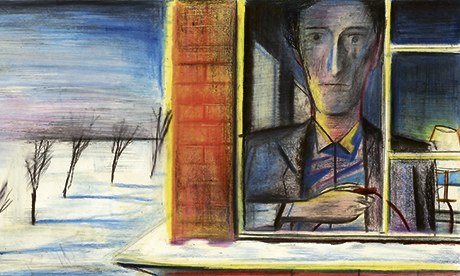

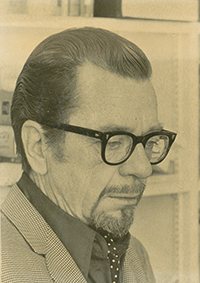

John Williams Photograph: The University of Denve Stoner is a farm boy, initially studying agriculture and a requirement of his course is to take a class in English literature. The students are set two Shakespeare plays, and then some sonnets, including the 73rd. Asked to elucidate the poem by an impatient and sardonic professor, Stoner finds himself tongue-tied and embarrassed, unable to say more than „It means … it means …“ And yet, something has happened within him: an epiphany rooted less in a moment of understanding than of not understanding. He has realised that there is something out there which, if he can seize it, will unlock not just literature but life itself; and in advance of such future understanding, he already feels his humanity awakened, and a new kinship with those around him. His life will change utterly from this moment: he will discover „a sense of wonder“ at grammar, and grasp how literature changes the world even as it describes it. He becomes a teacher,“which was simply a man to whom his book is true, to whom is given a dignity of art that has little to do with his foolishness or weakness or inadequacy as a man“. Towards the end of his life, when he has endured many disappointments, he thinks of academe as „the only life that had not betrayed him“. And he understands also that there is a continual battle between the academy and the world: the academy must keep the world, and its values, out for as long as possible.

John Williams Photograph: The University of Denve Stoner is a farm boy, initially studying agriculture and a requirement of his course is to take a class in English literature. The students are set two Shakespeare plays, and then some sonnets, including the 73rd. Asked to elucidate the poem by an impatient and sardonic professor, Stoner finds himself tongue-tied and embarrassed, unable to say more than „It means … it means …“ And yet, something has happened within him: an epiphany rooted less in a moment of understanding than of not understanding. He has realised that there is something out there which, if he can seize it, will unlock not just literature but life itself; and in advance of such future understanding, he already feels his humanity awakened, and a new kinship with those around him. His life will change utterly from this moment: he will discover „a sense of wonder“ at grammar, and grasp how literature changes the world even as it describes it. He becomes a teacher,“which was simply a man to whom his book is true, to whom is given a dignity of art that has little to do with his foolishness or weakness or inadequacy as a man“. Towards the end of his life, when he has endured many disappointments, he thinks of academe as „the only life that had not betrayed him“. And he understands also that there is a continual battle between the academy and the world: the academy must keep the world, and its values, out for as long as possible.

Stoner is a son of the soil – patient, earnest and enduring – who moves unprepared into the city and the world. Williams is wonderful at human awkwardness, at physical and emotional shyness, at not speaking your mind or your heart, either because you cannot articulate them, or because you simply cannot follow what has happened, or both:

And so, like many others, their

honeymoon was a failure; yet

they would not admit this to

themselves, and they did not

realise the significance of the

failure until long afterward.

Good things do happen in Stoner’s life, but they all end badly. He relishes teaching students, but his career is stymied by a malevolent head of department; he falls in love and marries, but knows within a month that the relationship is a failure; he adores his daughter, but she is turned against him; he is given sudden new life by an affair, but finds love vulnerable to outside interference, just as the academy is vulnerable to the world. Aged 42, he reflects that „he could see nothing before him that he wished to enjoy and little behind him that he cared to remember“.

Though he is allowed small victories towards the end of the novel, they are pyrrhic ones. The pains of lost and thwarted love have tested Stoner’s reserves of stoicism to the full; and you might well conclude that his life must be accounted pretty much a failure. But, if so, you would not have Williams on your side. In one of his rare interviews, he commented of his protagonist: „I think he’s a real hero. A lot of people who have read the novel think that Stoner had such a sad and bad life. I think he had a very good life. He had a better life than most people do, certainly. He was doing what he wanted to do, he had some feeling for what he was doing, he had some sense of the importance of the job he was doing … The important thing in the novel to me is Stoner’s sense of a job … a job in the good and honourable sense of the word. His job gave him a particular kind of identity and made him what he was.“

Writers often disagree with readers about the emphasis of their work. Even so, it’s a surprise that Williams seems surprised that others might find Stoner’s life „sad“. He himself was more than aware of its likely effect. In that letter to Rodell, he writes: „One afternoon a few weeks ago, I walked in on my typist (a junior history major, and pretty average, I’m afraid) while she was finishing typing chapter 15, and discovered great huge tears coursing down her cheeks. I shall love her for ever.“

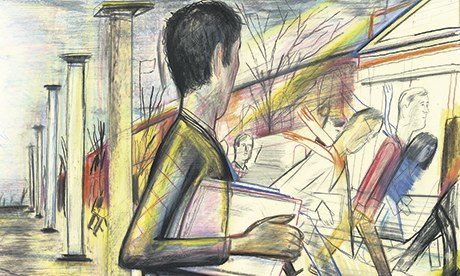

Illustration by Yann Kebbi The sadness of Stoner is of its own particular kind. It is not, say, the operatic sadness of The Good Soldier, or the grindingly sociological sadness of New Grub Street. It feels a purer, less literary kind, closer to life’s true sadness. As a reader, you can see it coming in the way you can often see life’s sadness coming, knowing there is little you can do about it. Except – since you are a reader – you can at least defer it. I found that when reading Stoner for the first time, I would limit myself most days to 30 or 40 pages, preferring to put off until the morrow knowledge of what Stoner might next have to bear.

Illustration by Yann Kebbi The sadness of Stoner is of its own particular kind. It is not, say, the operatic sadness of The Good Soldier, or the grindingly sociological sadness of New Grub Street. It feels a purer, less literary kind, closer to life’s true sadness. As a reader, you can see it coming in the way you can often see life’s sadness coming, knowing there is little you can do about it. Except – since you are a reader – you can at least defer it. I found that when reading Stoner for the first time, I would limit myself most days to 30 or 40 pages, preferring to put off until the morrow knowledge of what Stoner might next have to bear.

The title – suggested by his American publishers – remains unexciting (though better, probably, than Williams’s first attempts: A Flaw of Light and The Matter of Love). Still, a book makes its title, rather than the other way round. And what the book has turned into is more than one more forgotten work gratifyingly exhumed. When a novel by, say, Henry Green or Patrick Hamilton is „rediscovered“, the graph of sales usually forms a brief, respectable hump before returning again to the horizontal. Stoner first went into Vintage in 2003, after McGahern had recommended it to the publisher Robin Robertson. In the decade up to 2012, it sold 4,863 copies, and by the end of last year was trundling along in print-on-demand. This year, up to the end of November, it has sold 164,000 copies, with the vast majority – 144,000 of them – coming since June.

It was the novel’s sudden success in France in 2011 that alerted other publishers to its possibilities; since then it has sold 200,000 copies in Holland and 80,000 in Italy. It has been a bestseller in Israel, and is just beginning to take off in Germany. Though Williams died in 1994, his widow is, happily, still alive to enjoy the worldwide royalties. Rights have now been sold in 21 countries, and Stoner is soon to be launched on China.

There is a further oddity about the revival of Stoner: it seems to be a purely European (and Israeli) phenomenon so far. Bret Easton Ellis has tweeted its praise, and Tom Hanks has applauded it, but these have been rare American voices in its favour. When I asked around among my American literary friends, some had simply never heard of the novel, nor of Williams, and others were lukewarm in their response. Lorrie Moore’s praise was carefully qualified: „Stoner is such an interesting phenomenon. It is a terrific and terrifically sad little book, but the way it has taken off in the UK is a bit of a head-scratcher for most American writers, who find it lovely, flawed, engagingly written, and minor rather than great.“

This disparity needs some explanation, and I’m not sure I can supply it. Perhaps Europeans are more open to the quietness of the novel than Americans. Perhaps Americans have read more novels that resemble Stoner than we have (though what they might be I can’t think). Perhaps American readers don’t like its lack of „optimism“ (there is no shortage of pessimism in American literature, but the national character is one of striving, of altering circumstances, rather than accepting them). Or perhaps they are merely lagging behind us, and will soon catch up. When I put these points to the novelist Sylvia Brownrigg, she responded: „The reticence seems very not American to me. In spite of the American setting, the character himself feels more English, or European – opaque, fundamentally decent,and passive … Perhaps the lack of the novel’s taking hold in the US is because it doesn’t feel like One of Ours? We’re such a country of maximalists, noisy ones, and though obviously there are exceptions, even our minimalists are not spare and sad in this particular way … Another thought crossed my mind: that there is little drinking in Stoner. I wonder if American characters who are self-contained and stoical (I am thinking of Carver, or Richard Yates) more often have to be alcoholics to rein themselves in, and accept their disappointments.“

Whatever the reasons for its cooler reception in the US, I don’t agree that the novel is „minor“; nor do I think it is „great“ in the way that, say, Gatsby or Updike’s Rabbit quartet are great. I think Williams himself got it right: it is „substantially good“. It is good, and it has considerable substance, and gravity, and continuation in the mind afterwards. And it is a true „reader’s novel“, in the sense that its narrative reinforces the very value of reading and study. Many will be reminded of their own lectoral epiphanies, of those moments when the magic of literature first made some kind of distant sense, first suggested that this might be the best way of understanding life. And readers are also aware that this sacred inner space, in which reading and ruminating and being oneself happen, is increasingly threatened by what Stoner refers to as „the world“ – which is nowadays full of hectic interference with, and constant surveillance of, the individual. Perhaps something of this anxiety lies behind the renaissance of the novel. But you should – indeed must – find out for yourself.

Sunday TImes, 16 June 2013

This is the story of the greatest novel you have never read. I can be confident you have never read it because so few people have. In recent weeks, I have come across academics specialising in American literature who have never even heard of it. Yet it is, without question, one of the great novels in English of the 20th century. It’s certainly the most surprising.

Stoner, by John Williams, was first published in 1965. It was his third novel and was barely noticed. He published one more: Augustus, in 1972. That at least won the National Book award, though there was a dispute in the jury and Williams had to share the prize with John Barth, a now largely unread postmodernist. Williams died in 1994, never having enjoyed, apart from that prize, any real success, in spite of the praise heaped on it by the eminent and famous.

“Very few novels in English, or literary productions of any kind, have come anywhere near its level for human wisdom or as a work of art,” said the novelist and scientist CP Snow in 1973.

“Stoner… is a perfect novel,” wrote the critic Morris Dickstein, “so well told and beautifully written, so deeply moving, that it takes your breath away.”

“It’s simply a novel about a guy,” says Tom Hanks (yes, the Tom Hanks), “who goes to college and becomes a teacher. But it’s one of the most fascinating things you’ve ever come across.” (This quote troubles me. If Hollywood knows about it, a movie may be made, and — the supreme nightmare — it might be directed by Baz Luhrmann.)

Stoner’s lack of success has baffled many. “Why isn’t this book more famous?” asked Snow. Ian McEwan, a recent reader, emails me to say: “I’m amazed a novel this good escaped general attention for so long.” The essayist Geoff Dyer has just read the book on the recommendation of a friend, the novelist and poet Adam Foulds. He thinks the title doesn’t help — it’s the hero’s surname, but nowadays might be taken to mean the book is about a dope-smoker. “Also,” Dyer adds, “it’s such a quiet book, it’s not entirely surprising it didn’t take the publishing world by storm.” Stoner, in short, is unmarketable — always, in my view, a good sign.

Yet finally this quiet book seems to be breaking through. The process may have begun in 2006, with the publication of Stoner in a New York Review of Books edition, which included an exquisite introduction by the Irish novelist John McGahern. He spoke of the “plain prose, which seems to reflect effortlessly every shade of thought and feeling”, and of “the passion of the writing masked by a coolness and clarity of intellect”. Exactly.

This became a Vintage Classics edition, which was then widely translated; and suddenly European readers were flocking to Stoner. It’s been top of the charts in the Netherlands and is selling well in France, Spain and Italy. This wave is now lapping at our shores. Vintage is giving away the first chapter with the ebook version of The Great Gatsby, a sure sign that the publishers think they have a winner.

I first read Stoner about three years ago and could find nobody to discuss it with except the friend who recommended it. Now I am finding people who have read it in the past few weeks. I send them off to read Butcher’s Crossing, Williams’s anti-western, which anticipates Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, and Augustus, an epistolary novel about Augustus Caesar. Both are masterpieces; both are utterly different from Stoner. Williams’s range is breathtaking, although Dickstein detects common themes: “A young man’s initiation, vicious male rivalries, subtler tensions between men and women, fathers and daughters, and finally a bleak sense of disappointment, even futility.”

Stoner tells the story of the whole life of William Stoner (born 1891, dies 1956), a farmer’s son who becomes a teacher of literature at the University of Missouri. We know from the first page that his life is entirely forgettable, that nothing grand or remarkable happens to him, and that he is hardly remembered by those who knew him. It is a life you or I or anybody could have lived. I’ll leave the next part of the explanation to McEwan’s email.

“Great authority in the prose, beautiful, sad, utterly convincing account of an entire life, of how a gifted man can drift into obscurity, can almost lift himself into the clear light of happiness in love, then fall back. The awful wife, the disappointed hopes for the daughter, the bitter lifelong persecution by a fellow academic — it sounds depressing when these elements are listed, but Williams makes a thing of beauty out of them. The subjective rendering of Stoner’s death is unsurpassed in modern literature.”

There are two great positives in Stoner’s life: both are forms of love. The first is his discovery of literature, beautifully dramatised in a scene when a teacher asks him what he thinks is the meaning of Shakespeare’s sonnet That Time of Year Thou Mayst in Me Behold. Stoner cannot answer because he is overwhelmed. It means everything. The teacher understands his response.

“It’s love, Mr Stoner,” he says, “you are in love, it’s as simple as that.”

After that, he cannot go back to the farm. He tells his father, whose face “received those words as a stone receives the repeated blows of a fist”. You will gasp a lot when reading Stoner.

The second is human love: first, paternal, for the daughter of his unhappy marriage; then erotic. He has an adulterous affair, an episode that bursts out of the hard, dull grind of his life with an astonishing spring-like freshness. In this he realises love is “a human act of becoming, a condition that was invented and modified moment by moment and day by day, by the will and the intelligence and the heart”. But, of course, it cannot last.

This brightness and beauty is set against the ordinariness of his work, which turns into suffering when he finds himself victimised by a student and fellow teacher, a process that destroys his status and blocks his career. Stoner’s death, as McEwan notes, is one of the finest and most remarkable things in this book. In the silent suffering of his life, he has achieved what Dyer calls “resignation as a form of defiance”. In dying, he reviews his life and repeatedly returns to the question: “What did you expect?” Finally, his slowly evaporating self becomes a sort of floating brightness, and the whole tragedy resolves itself into nothing.

Stoner just lives and dies like you and me, and everything that happens just lies in front of us, in plain sight. This is a level of simplicity that it takes a genius to achieve. As a result, the book is an agonising and beautiful read, but also very easy.

“It’s a great entry-level book,” says the critic DG Myers. “It’s the best book to give to somebody who is turning to serious literature for the first time.”

The novel features no Nabokovian trickery, no Jamesian twists and turns, no Conradian weight of significance, no Fordian contortions; and there is certainly no fancy phrase-making or desperate offers of redemption to the hero

Placing this novel is hard. Dyer detects DH Lawrence in the scene in which Stoner’s previously frigid wife suddenly succumbs to an erotic frenzy. I can only link him to a certain strand in Russian literature — the struggling “little” people, the hopeless clerical figures in Dostoevsky, Chekhov and Tolstoy. Sarah Churchwell, at the University of East Anglia, is reminded of the novels of Paula Fox and Willa Cather. She is also pleased that Vintage is matching Stoner with the ebook of The Great Gatsby. “Stylistically the two books couldn’t be more different, but they are both brief novels that demonstrate an abiding love of language and are about an inarticulate faith in life’s possibilities and the inevitability of disillusionment. But they are about idealists (and ideals), and about disappointment, the poignancy of noble failure.”

She adds: “Stoner is one of the saddest books I’ve read in some time. It is not a bleak or a grim novel, although it has moments of both. But that sense of integrity, virtue, quiet heroism — that is sustaining. It’s just about being true to yourself, in the end, and the consolation that brings. A lovely, sad little masterpiece, the kind that colours your mood for days.”

The real roots seem to lie in Williams’s life. Like Stoner, he was brought up on a farm (in Texas) and, after serving in the war, he became an academic at the University of Denver. Also like Stoner, he produced an academic book, an anthology of Renaissance poetry. Myers tells me this brought him into conflict with the great critic Yvor Winters, who accused him of plagiarism, a very Stonerish incident.

Myers says, however, that the book is more biography than autobiography — the real model for Stoner being the poet and scholar JV Cunningham. The story of Cunningham’s marriage to the poet Barbara Gibbs — they had one daughter — seems to match that of Stoner’s to the complex and terrible Edith.

Williams died at his home in Fayetteville, Arkansas, on March 3, 1994. He had written four novels — many people say three, but they miss out his first, Nothing But the Night — and two collections of poetry. The poems are sound but ordinary. The most commonly seen picture of him shows a dandyish man: he sports a polka-dot cravat, well-barbered and brushed hair, and a carefully tended beard. Yet the face looks sad, wounded, perhaps defeated. In spite of that, in spite of everything, this story of the greatest book you have never read is not a sad one. Though Stoner is a tragedy, it is not a book that will sadden the careful reader.

“There is entertainment of a very high order to be found in Stoner,” McGahern wrote, “what Williams himself describes as ‘an escape into reality’, as well as pain and joy. The clarity of the prose is in itself an unadulterated joy.” Williams, when asked whether literature should be entertaining, replied: “Absolutely. My God, to read without joy is stupid.”

Justice is now being done to Williams and to Stoner, who, finally, has the happy ending he so richly deserved.

“I think he’s a real hero. A lot of people who have read the novel think that Stoner had such a sad and bad life. I think he had a very good life. He had a better life than most people do, certainly. He was doing what he wanted to do, he had some feeling for what he was doing, he had some sense of the importance of the job he was doing. He was a witness to values that are important…The important thing in the novel to me is Stoner’s sense of a job. Teaching to him is a job – a job in the good and honourable sense of the word. His job gave him a particular kind of identity and made him what he was.” (John Williams)

| SONNET 73 | PARAPHRASE |

| That time of year thou mayst in me behold | In me you can see that time of year |

| When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang | When a few yellow leaves or none at all hang |

| Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, | On the branches, shaking against the cold, |

| Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. | Bare ruins of church choirs where lately the sweet birds sang. |

| In me thou seest the twilight of such day | In me you can see only the dim light that remains |

| As after sunset fadeth in the west, | After the sun sets in the west, |

| Which by and by black night doth take away, | Which is soon extinguished by black night, |

| Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest. | The image of death that envelops all in rest. |

| In me thou see’st the glowing of such fire | I am like a glowing ember |

| That on the ashes of his youth doth lie, | Lying on the dying flame of my youth, |

| As the death-bed whereon it must expire, | As on the death bed where it must finally expire, |

| Consum’d with that which it was nourish’d by. | Consumed by that which once fed it. |

| This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong, | This you sense, and it makes your love more determined |

| To love that well which thou must leave ere long. | Causing you to love that which you must give up before long. |

that time of year (1): i.e., being late autumn or early winter.

When yellow leaves… (2): compare Macbeth (5.3.23) „my way of life/is fall’n into the sere, the yellow leaf.“

Bare ruin’d choirs (4): a reference to the remains of a church or, more specifically, a chancel, stripped of its roof and exposed to the elements. The choirs formerly rang with the sounds of ’sweet birds‘. Some argue that lines 3 and 4 should be read without pause — the ‚yellow leaves‘ shake against the ‚cold/Bare ruin’d choirs.‘ If we assume the adjective ‚cold‘ modifies ‚Bare ruin’d choirs‘, then the image becomes more concrete — those boughs are sweeping against the ruins of the church. Some editors, however, choose to insert ‚like‘ into the opening of line 4, thus changing the passage to mean ‚the boughs of the yellow leaves shake against the cold like the jagged arches of the choir stand exposed to the cold.‘ Noted 18th-century scholar George Steevens commented that this image „was probably suggested to Shakespeare by our desolated monasteries. The resemblance between the vaulting of a Gothic isle [sic] and an avenue of trees whose upper branches meet and form an arch overhead, is too striking not to be acknowledged. When the roof of the one is shattered, and the boughs of the other leafless, the comparison becomes more solemn and picturesque“ (Quoted in Smith, p. 148).

black night (7): a metaphor for death itself. As ‚black night‘ closes in around the remaining light of the day, so too does death close in around the poet.

Death’s second self (8): i.e. ‚black night‘ or ’sleep.‘ Macbeth refers to sleep as „The death of each day’s life“ (2.2.49).

In me thou see’st…was nourish’d by (9-12): The following is a brilliant paraphrase by early 20th-century scholar Kellner: „As the fire goes out when the wood which has been feeding it is consumed, so is life extinguished when the strength of youth is past.“ (Quoted in Rollins, p. 191)

that (12): i.e., the poet’s desires.

This (14): i.e., the demise of the poet’s youth and passion.

To love that well (12): The meaning of this phrase and of the concluding couplet has caused much debate. Is the poet saying that the young man now understands that he will lose his own youth and passion, after listening to the lamentations in the three preceding quatrains? Or is the poet saying that the young man now is aware of the poet’s imminent demise, and this knowledge makes the young man’s love for the poet stronger because he might soon lose him? What must the young man give up before long — his youth or his friend? For more on this dilemma please see the commentary below.

_____

Sonnets 71-74 are typically analyzed as a group, linked by the poet’s thoughts of his own mortality. However, Sonnet 73 contains many of the themes common throughout the entire body of sonnets, including the ravages of time on one’s physical well-being and the mental anguish associated with moving further from youth and closer to death. Time’s destruction of great monuments juxtaposed with the effects of age on human beings is a convention seen before, most notably in Sonnet 55.

The poet is preparing his young friend, not for the approaching literal death of his body, but the metaphorical death of his youth and passion. The poet’s deep insecurities swell irrepressibly as he concludes that the young man is now focused only on the signs of his aging — as the poet surely is himself. This is illustrated by the linear development of the three quatrains. The first two quatrains establish what the poet perceives the young man now sees as he looks at the poet: those yellow leaves and bare boughs, and the faint afterglow of the fading sun. The third quatrain reveals that the poet is speaking not of his impending physical death, but the death of his youth and subsequently his youthful desires — those very things which sustained his relationship with the young man.

Throughout the 126 sonnets addressed to the young man the poet tries repeatedly to impart his wisdom of Time’s wrath, and more specifically, the sad truth that time will have the same effects on the young man as it has upon the poet. And as we see in the concluding couplet of Sonnet 73, the poet has this time succeeded. The young man now understands the importance of his own youth, which he will be forced to ‚leave ere long‘ (14).

It must be reiterated that some critics assume the young man ‚perceives‘ not the future loss of his own youth, but the approaching loss of the poet, his dear friend. This would then mean that the poet is speaking of his death in the literal sense. Feuillerat argues that

Even if we make allowance for the exaggeration which is every poet’s right, Shakespeare was not young when he wrote this sonnet. It is overcast by the shadow of death and belongs to a date perhaps not far from 1609. (The Composition of Shakespeare’s Plays, p. 72)

This interpretation is less popular because it is now generally accepted that all 154 sonnets were composed before 1600, so Shakespeare would have been no older than thirty-six. However, the sonnets were not initially printed in the order we now accept them, and an error in sequence is very possible.

Sonnet 73 is one of Shakespeare’s most famous works, but it has prompted both tremendous praise and sharp criticism. Included here are excerpts from commentaries by two noted Shakespearean scholars, John Barryman and John Crowe Ransom:

The fundamental emotion [in Sonnet 73] is self-pity. Not an attractive emotion. What renders it pathetic, in the good instead of the bad sense, is the sinister diminution of the time concept, quatrain by quatrain. We have first a year, and the final season of it; then only a day, and the stretch of it; then just a fire, built for part of the day, and the final minutes of it; then — entirely deprived of life, in prospect, and even now a merely objective „that,“ like a third-person corpse! — the poet. The imagery begins and continues as visual — yellow, sunset, glowing — and one by one these are destroyed; but also in the first quatrain one heard sound, which disappears there; and from the couplet imagery of every kind is excluded, as if the sense were indeed dead, and only abstract, posthumous statement is possible. A year seems short enough; yet ironically the day, and then the fire, makes it in retrospect seem long, and the final immediate triumph of the poem’s imagination is that in the last line about the year, line 4, an immense vista is indeed invoked — that the desolate monasteries strewn over England, sacked in Henry’s reign, where ‚late‘ — not so long ago! a terrible foreglance into the tiny coming times of the poem — the choirs of monks lifted their little and brief voices, in ignorance of what was coming — as the poet would be doing now, except that this poem knows. Instinct is here, after all, a kind of thought. This is one of the best poems in English.

(John Berryman, The Sonnets)

*****

The structure is good, the three quatrains offering distinct yet equivalent figures for the time of life of the unsuccessful and to-be-pitied lover. But the first quatrain is the boldest, and the effect of the whole is slightly anti-climactic. Within this quatrain I think I detect a thing which often characterizes Shakespeare’s work within the metaphysical style: he is unwilling to renounce the benefit of his earlier style, which consisted in the breadth of the associations; that is, he will not quite risk the power of a single figure but compounds the figures. I refer to the two images about the boughs. It is one thing to have the boughs shaking against the cold, and in that capacity they carry very well the fact of the old rejected lover; it is another thing to represent them as ruined choirs where the birds no longer sing. The latter is a just representation of the lover too, and indeed a subtler and richer one, but the two images cannot, in logical rigor, co-exist. Therefore I deprecate shake against the cold. And I believe everybody will deprecate sweet. This term is not an objective image at all, but a term to be located at the subjective pole of the experience; it expects to satisfy a feeling by naming it (this is, by just having it) and is a pure sentimentalism.

(John Crowe Ransom, Shakespeare at Sonnets).

For more on how the sonnets are grouped, please see the general introduction to Shakespeare’s sonnets.